The central argument of this article is that the 1947 Partition of India and the 1948 displacement of Palestinians (the NakbaNakba Full Description:

Arabic for “The Catastrophe.” It refers to the mass expulsion and flight of hundreds of thousands of Palestinians from their homes during the conflict. It is not merely a historical event but describes the ongoing condition of statelessness and dispossession faced by Palestinian refugees. The Nakba marks the foundational trauma of Palestinian identity. During the fighting that established the State of Israel, a vast majority of the Arab population in the territory either fled out of fear or were forcibly expelled by militias and the new army. Their villages were subsequently destroyed or repopulated to prevent their return.

Read more) are not merely parallel historical tragedies but foundational “double displacements.” They each involved a primary, violent expulsion followed by a secondary, systemic dispossession—the denial of the right to return, the legal seizure of property, and the erasure of historical belonging in the new national orders. Created within months of each other by the retreat of the British Empire, these twin crises remade the political geography of Asia and the Middle East, manufactured the world’s two largest and most enduring refugee populations, and established toxic legacies of irredentism, militarization, and contested identity that define these regions to this day. This is the story of how lines drawn on maps fractured societies and how the consequences of those fractures continue to shape our world.

The Fracturing: Two Partitions, One Imperial Retreat

The years 1947 and 1948 represent the bloody climax of Britain’s imperial disengagement from its most volatile possessions. In both South Asia and Palestine, the British faced intractable conflicts they could no longer manage, leaving behind hastily conceived partition plans that served as exit strategies rather than durable political solutions.

The Road to Division: A Comparative Timeline

Mandatory Palestine (1917-1947)

· 1917: The Balfour Declaration commits Britain to support “a national home for the Jewish people” in Palestine, conflicting with promises of independence to Arab allies.

· 1920-1948: The British Mandate oversees growing Jewish immigration, swelling the population from under 10% to over 30% by 1947.

· 1937: The Peel Commission first proposes partition; Palestinian Arabs reject it, Zionists give provisional approval.

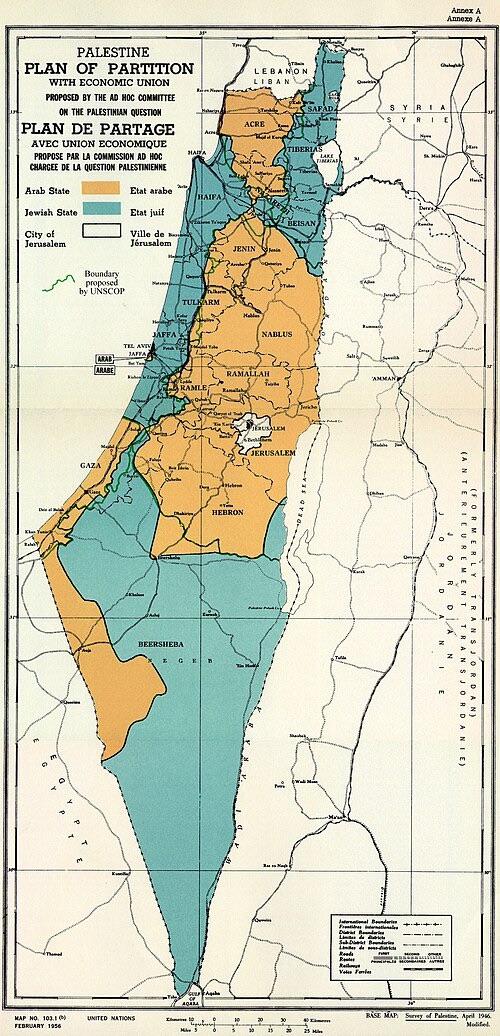

· 29 November 1947: UN General Assembly adopts Resolution 181 (II), the Partition Plan, with 33 votes in favor, 13 against, and 10 abstaining. The plan allocates approximately 56% of the land to a Jewish state and 43% to an Arab state, with Jerusalem as an international zone, despite Palestinian Arabs forming two-thirds of the population.

British India (1858-1947)

· Late 19th Century: The rise of organized Hindu and Muslim political consciousness.

· 1940: The Muslim League’s Lahore ResolutionLahore Resolution Full Description:A landmark political statement adopted by the Muslim League in 1940. While it did not explicitly use the word “Pakistan,” it called for the creation of “independent states” for Muslims, serving as the formal point of departure for the separatist movement. The Lahore Resolution fundamentally changed the nature of the Indian political dialogue. It moved the Muslim League’s demand from constitutional safeguards within India to territorial sovereignty outside of it. It declared that no constitutional plan would be workable unless it recognized the Muslim-majority zones as independent entities.

Critical Perspective:Historians debate whether this was a final demand or a “bargaining chip” intended to secure a loose federation. The ambiguity of the text (referring to “states” in the plural) suggests that the final form of Pakistan was not yet decided. However, once the demand was made public, it galvanized the Muslim masses, creating a momentum that the leadership ultimately could not control, making compromise impossible.

Read more formally demands independent states for Muslim-majority areas.

· 1946-1947: Mounting communal violence and the failure of a unified cabinet make partition seem inevitable to the British.

· 3 June 1947: Viceroy Lord Mountbatten announces the Partition Plan, based on the “Radcliffe LineRadcliffe Line Full Description:The Radcliffe Line represents the ultimate act of colonial negligence. Tasked with dividing a subcontinent, the boundary commission, led by Cyril Radcliffe, finalized the borders in isolation, often cutting through villages, agricultural systems, and communities without regard for ground realities.

Consequences:

Arbitrary Division: The line was kept secret until after independence was declared, leading to panic and uncertainty.

Mass Migration: Millions found themselves on the “wrong” side of the border, triggering one of the largest and bloodiest forced migrations in history.

Legacy of Conflict: The ambiguous and insensitive drawing of the line planted the seeds for perpetual border disputes and regional instability.

.”

· 14-15 August 1947: Transfer of Power. India and Pakistan become independent dominions.

The Nature of the Divide

The fundamental difference lay in the basis for partition and the international posture toward it.

· In Palestine, partition was an internationally sanctioned but locally rejected act. The UN plan was a geopolitical compromise, granting a majority of the land to the Jewish minority, in part as a response to the Holocaust. Palestinian Arabs and the surrounding Arab states saw it as a profound injustice that violated the principle of self-determinationSelf-Determination Full Description:Self-Determination became the rallying cry for anti-colonial movements worldwide. While enshrined in the UN Charter, its application was initially fiercely contested. Colonial powers argued it did not apply to their imperial possessions, while independence movements used the UN’s own language to demand the end of empire.

Critical Perspective:There is a fundamental tension in the UN’s history regarding this term. While the organization theoretically supported freedom, its most powerful members were often actively fighting brutal wars to suppress self-determination movements in their colonies. The realization of this right was not granted by the UN, but seized by colonized peoples through struggle. for the majority population. The Zionist leadership accepted it tactically, with figures like David Ben-Gurion viewing it as a stepping stone.

· In India, partition was a locally negotiated but internationally unmanaged divorce. It was driven by the political failure to reconcile the “two-nation theory” with a unified state. While the Indian National CongressIndian National Congress The principal political party of the Indian independence movement. Founded in 1885, it sought to represent all Indians regardless of religion, leading the struggle against British rule under a secular, nationalist platform. The Indian National Congress was a broad coalition that utilized mass mobilization and civil disobedience to challenge the British Raj. Led by figures like Gandhi and Nehru, it advocated for a unified, democratic, and secular state. It consistently rejected the Two-Nation Theory, arguing that religion should not be the basis of nationality.

Critical Perspective:Despite its secular ideology, the Congress leadership was predominantly Hindu, and its cultural symbolism (often drawn from Hindu tradition) alienated many Muslims. Critics argue that the Congress’s refusal to form coalition governments with the League in 1937 was a strategic error that pushed the League toward separatism. Its inability to accommodate Muslim political anxieties within a federal framework ultimately contributed to the inevitability of Partition.

Read more opposed division until the last moment, the final plan was brokered between British, Congress, and Muslim League elites. There was no UN vote, no international peacekeepingPeacekeeping

Full Description:A mechanism not originally explicitly defined in the Charter, involving the deployment of international military and civilian personnel to conflict zones. Known as the “Blue Helmets,” they monitor ceasefires and create buffer zones to allow for diplomatic negotiations. Peacekeeping was an improvisation developed to manage Cold War conflicts that the Great Powers could not agree to solve forcibly. It operates on the principles of consent (the host country must agree), impartiality, and the non-use of force except in self-defense.

Critical Perspective:While often celebrated, peacekeeping is often criticized for “freezing” conflicts rather than solving them. By stabilizing the status quo, it can inadvertently remove the pressure for political solutions, leading to “forever wars” where the UN presence becomes a permanent feature of the landscape. Furthermore, peacekeepers have faced severe criticism for failures to protect civilians and for sexual exploitation and abuse in host communities.

Read more force—just a rushed British departure and the handing over of sovereignty to two hostile successor states.

In both cases, the actual borders were poorly defined, based on outdated maps and census data, and were kept secret until the day of independence, maximizing confusion and panic. The lines did not merely divide territory; they cleaved through integrated economies, shared cultural zones, and millions of lives.

The Great Unraveling: Mechanics of Mass Displacement

The violence that followed the announcement of these borders was of a cataclysmic scale, but the mechanics of displacement revealed both stark similarities and critical differences.

Scale and Speed

· India (1947): An estimated 14-18 million people crossed the new borders in under a year, constituting the largest mass migration in human history. The violence was intensely communal, with massacres, abductions, and forced conversions occurring on all sides. Trains arriving from across the border, filled with corpses, became grim symbols of the partition.

· Palestine (1947-1949): Approximately 750,000 to 800,000 Palestinian Arabs—over half the Arab population of the territory that became Israel—fled or were expelled from their homes. This exodus unfolded in phases, intensifying after the UN vote and peaking during the 1948 Arab-Israeli War.

Causes: A Spectrum of Coercion

The historiography of both displacements grapples with the relative weight of “flight” versus “expulsion.” Modern scholarship acknowledges a complex mix of factors, where fear and direct force were inseparable.

· Fear and Psychological Warfare: In both cases, terrifying precedents were set. In Palestine, the Deir Yassin massacreDeir Yassin Massacre

Full Description:The killing of over 100 Palestinian civilians in the village of Deir Yassin on April 9, 1948, by Irgun and Lehi paramilitaries. News of the brutality spread rapidly, causing panic among the Palestinian population and accelerating the mass flight of refugees. Deir Yassin was a pivotal psychological turning point. The village had actually signed a non-aggression pact with its Jewish neighbors but was targeted to break the morale of Jerusalem’s Arab defenders. The massacre involved mutilation and the parading of survivors through Jerusalem.

Critical Perspective:Critically, Deir Yassin was weaponized by both sides. Jewish militias amplified the horror to terrify other villages into fleeing (“psychological warfare”), while Arab leaders broadcast the atrocity to shame Arab armies into intervening. The tragedy is that this broadcasting of the massacre inadvertently assisted the Zionist goal of emptying the land by triggering a panic-induced exodus.

Read more of April 1948, where over 100 villagers were killed by Zionist militias, was widely publicized to panic surrounding populations into flight. In India, the scale of retaliatory violence created a self-perpetuating cycle of terror where minorities felt they had no choice but to flee preemptively.

· Direct Military Expulsion: In Palestine, scholars like Ilan Pappé and Benny Morris document systematic operations. Plan Dalet (Plan D), launched by the HaganahHaganah

Full Description:The primary Jewish paramilitary organization during the British Mandate. It evolved from a decentralized defense force into a conventional army, eventually forming the core of the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) after independence. The Haganah (“The Defense”) was the military wing of the mainstream Zionist labor movement. Unlike the more radical Irgun or Lehi, it generally cooperated with British authorities until the post-war period. It was responsible for organizing illegal immigration and, later, executing Plan Dalet.

Critical Perspective:The transformation of the Haganah illustrates the process of state-building. By absorbing or dismantling rival militias (sometimes violently, as in the Altalena Affair), the Haganah established the state’s monopoly on violence. However, its involvement in village expulsions challenges the myth of the “purity of arms” often associated with the IDF’s origins.

Read more in April 1948, aimed to secure territory for the Jewish state and often involved the conquest and clearing of Arab villages. Expulsion orders, house demolitions, and massacres were direct tools. In India, while there was no single military blueprint, the breakdown of law and order and the partisanship of local police and militia often led to the forced eviction of minority communities.

· The Collapse of Authority and Leadership: In both crises, the departure or impotence of the governing power (Britain) created a security vacuum. The flight of local elites and community leaders in early stages demoralized those left behind and removed a stabilizing force. In Palestine, the disarray and strategic failures of the Arab leadership and invading armies contributed to the collapse.

The result was the same: a landscape emptied of ancient communities, dotted with abandoned villages and looted homes, creating what Palestinian historian Elias Sanbar calls a “world obliterated”.

The Second Displacement: Legal Erasure and the Manufacture of Permanent Refugeehood

The physical expulsion was only the first act. The second, and in many ways more durable, displacement was administered by law and state policy, which systematically transformed refugees into permanent stateless populations.

The Legal Architecture of Non-Return

· In Israel, a series of laws passed between 1948 and 1950 sealed the fate of Palestinian refugees. The Absentees’ Property Law (1950) was the cornerstone, defining any Palestinian who had left their home after November 1947—even if they remained within Israel’s new borders—as an “absentee.” Their property (homes, land, bank accounts) was transferred to a state custodian and later used to settle Jewish immigrants. This legal fiction prevented the return of over 700,000 refugees and confiscated millions of dunams of land.

· In India and Pakistan, while no single law mirrored Israel’s Absentees’ Property Act, a de facto population transfer was ratified by the Inter-Dominion Agreements. Both governments agreed to take responsibility for the welfare of incoming refugees and to manage the disposal of “evacuee property” to facilitate resettlement. This bureaucratic process, though chaotic, legally validated the exchange and extinguished any formal right of returnRight of Return

Full Description:The political and legal principle asserting that Palestinian refugees and their descendants have an inalienable right to return to the homes and properties they were displaced from in 1948. It is anchored in UN Resolution 194 but remains the most intractable issue in peace negotiations. The Right of Return is central to Palestinian national identity. It argues that the refugee status is temporary and that justice requires restitution. For Israel, this demand is viewed as an existential threat; allowing millions of Palestinians to return would end Israel’s status as a Jewish-majority state.

Critical Perspective:This issue highlights the clash between individual rights and ethno-nationalism. International law generally supports the return of refugees to their country of origin. However, the conflict is trapped in a zero-sum game where the restoration of Palestinian rights is interpreted as the destruction of Israeli sovereignty.

Read more. Property left behind was forfeited.

The International Response: Contrasts in Refugee Regimes

The international community responded to these crises in fundamentally different ways, cementing their divergent trajectories.

· Palestinian Refugees: The UN created a separate, specialized agency: the UN Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA), established in 1949. UNRWA’s mandate uniquely defines Palestinian refugees to include their descendants, leading to a registered population that has grown from 750,000 to over 5 million today. Arab host states (except Jordan) largely denied them citizenship, keeping them in camps as a political symbol of the unresolved conflict and the demand for the “right of return” based on UN Resolution 194UN Resolution 194

Full Description:A resolution passed by the UN General Assembly in December 1948. It resolved that refugees wishing to return to their homes and live at peace with their neighbors should be permitted to do so at the earliest practicable date, and that compensation should be paid for the property of those choosing not to return. Resolution 194 established the legal framework for the refugee issue. It also established the Conciliation Commission for Palestine. While non-binding (like all General Assembly resolutions), it has been reaffirmed over 100 times, giving it significant customary legal weight.

Critical Perspective:The failure to implement Resolution 194 demonstrates the weakness of international law when it conflicts with the interests of a sovereign state backed by powerful allies. Israel’s admission to the UN was implicitly conditional on honoring this resolution, yet it has consistently rejected it, arguing that the return of hostile populations is a security impossibility.

The year 1948 marks a seismic turning point in the history of the Middle East, an event of such profound consequence that its legacy continues to fuel one of the world’s most intractable conflicts. For Israelis, it is celebrated as the “War of Independence,” a heroic victory that realized the centuries-old dream of a Jewish state in their ancient homeland, born from the ashes of the Holocaust. For Palestinians, it is known as the “Nakba” or “Catastrophe,” a traumatic period of mass displacement, dispossession, and the shattering of their national aspirations.

These two deeply held, and starkly contrasting, narratives of the same historical events form the bedrock of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The struggle is not merely over land and resources, but over history itself, with each side’s foundational story defining its identity, its grievances, and its vision for the future. Understanding this duality is crucial to comprehending the political, social, and psychological landscape of the region today.

The End of the British Mandate: Imperial Withdrawal and the Onset of War

The roots of the 1948 conflict can be traced to the impending collapse of British colonial rule in Palestine. After World War II, an exhausted Britain, facing escalating violence from both Arab and Jewish communities and mounting international pressure, sought to extricate itself from its mandate. Unable to reconcile the conflicting promises made to both sides, Britain turned the issue over to the newly formed United Nations. The British announcement of their intent to withdraw by May 15, 1948, created a power vacuum, setting the stage for a civil war between the two communities.

The UN Partition Plan of 1947: A Spark in a Tinderbox

In November 1947, the UN General Assembly passed Resolution 181, a plan to partition Palestine into independent Arab and Jewish states, with Jerusalem to be under international administration. The plan allocated approximately 55% of the land to the Jewish state, despite the Jewish population comprising about a third of the total and owning a small fraction of the land.

The Jewish Agency, representing the Zionist movement, accepted the plan as a basis for statehood. However, the Palestinian Arab leadership and the Arab League vehemently rejected it, viewing it as a violation of the rights of the Arab majority to self-determination in their homeland. Immediately following the UN vote, widespread violence erupted between Jewish and Arab militias in what became the first phase of the 1948 war.

The 1948 War: Nakba and Independence

Plan Dalet: A Blueprint for ConflictIn March 1948, the Zionist leadership formally adopted Plan Dalet (Plan D), a military strategy developed by the Haganah, the main Jewish paramilitary organization. The plan’s stated objective was to secure the territory of the proposed Jewish state in anticipation of an invasion by Arab armies. However, its implementation involved taking control of and, in many cases, depopulating and destroying Palestinian villages and urban centers both within and outside the borders of the UN plan. The historical interpretation of Plan Dalet is highly contentious; some scholars view it as a defensive measure, while others see it as a blueprint for the systematic ethnic cleansing of Palestine.

The Palestinian Nakba: A National TraumaFor Palestinians, the period from late 1947 through 1949 is known as the Nakba, or “catastrophe.” This period witnessed the displacement of hundreds of thousands of Palestinian Arabs who either fled the violence or were forcibly expelled from their homes by Zionist militias and later the Israeli army. Several massacres of Palestinian civilians, most infamously at Deir Yassin in April 1948, fueled an atmosphere of terror that hastened the exodus. Over 500 Palestinian towns and villages were depopulated and subsequently destroyed. The Nakba represents the fragmentation of Palestinian society and the loss of their homeland, a foundational trauma that continues to define Palestinian identity and political goals.

Arab States’ Intervention and the Widening WarOn May 14, 1948, as the British Mandate expired, David Ben-Gurion declared the establishment of the State of Israel. The following day, armies from five Arab nations—Egypt, Transjordan (Jordan), Syria, Lebanon, and Iraq—invaded, officially beginning the second phase of the conflict, the 1948 Arab-Israeli War. The stated goal of the Arab states was to prevent the partition of Palestine and defend the Arab population. However, the Arab armies were often poorly coordinated and driven by conflicting political agendas, which hampered their military effectiveness.

The Aftermath: A New Reality

The Palestinian Refugee CrisisThe 1948 war created one of the world’s longest-standing refugee crises. The hundreds of thousands of Palestinians who were displaced sought refuge in the West Bank, the Gaza Strip, and neighboring Arab countries like Lebanon, Syria, and Jordan, often living in makeshift camps. In December 1948, the UN General Assembly passed Resolution 194, which resolved that “refugees wishing to return to their homes and live at peace with their neighbours should be permitted to do so.” Israel, however, has consistently refused to allow the return of refugees, and their fate remains a central and unresolved issue in the conflict.

The 1949 Armistice Agreements: A Frozen ConflictThe fighting largely concluded with the signing of armistice agreements between Israel and Egypt, Lebanon, Jordan, and Syria in 1949. These agreements were not peace treaties but military ceasefires that established demarcation lines, which became known as the “Green Line.” These lines left Israel in control of 78% of historic Palestine, significantly more territory than allocated by the UN Partition Plan. Egypt took control of the Gaza Strip, and Transjordan annexed the West Bank. The armistice agreements effectively froze the conflict, creating a tense and unstable status quo that would last until the 1967 war.

Israel’s Transformation: State-Building and ImmigrationFor Israel, victory in the 1948 war was a defining moment of state-building. The new state established its political institutions, including the Knesset (parliament), and rapidly developed its military. The war also triggered a massive wave of Jewish immigration, not only of Holocaust survivors from Europe but also of hundreds of thousands of Jews from Arab countries who faced increasing hostility and were compelled to leave their homes. This influx of diverse populations profoundly shaped Israeli society and its demographic landscape.

The Arab World After 1948: Political UpheavalThe defeat in the 1948 war was a deeply humiliating event for the Arab world, contributing to widespread political instability and upheaval. The loss, known as “al-Nakba” in the Arab world as well, discredited the old ruling elites and fueled the rise of new, more radical nationalist movements and military regimes in countries like Egypt and Syria. The Palestinian cause became a central and unifying issue in regional politics, though often manipulated by Arab leaders for their own ends.

The Legacy of 1948: The Politics of Memory

The events of 1948 are not merely historical; they are a living legacy that shapes the present-day reality of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The competing narratives of “Independence” and “Nakba” are central to the national identity of both peoples. Israeli identity is deeply rooted in the narrative of a miraculous victory against overwhelming odds and the establishment of a safe haven for the Jewish people. Palestinian identity is inextricably linked to the experience of loss, displacement, and the ongoing struggle for self-determination and the right of return. These foundational narratives are passed down through generations, taught in schools, and commemorated annually, reinforcing a sense of historical grievance and shaping the political goals of each side. The inability to acknowledge or reconcile these conflicting memories remains a fundamental obstacle to a just and lasting peace.

Timeline of Key Events

November 29, 1947: The UN General Assembly adopts Resolution 181, the Partition Plan for Palestine. Violence erupts between Jewish and Arab communities.

March 10, 1948: Zionist leadership formally adopts Plan Dalet.

April 9, 1948: The Deir Yassin massacre takes place, contributing to the flight of Palestinians.

May 14, 1948: The British Mandate for Palestine expires. David Ben-Gurion proclaims the establishment of the State of Israel.

May 15, 1948: Armies from Egypt, Transjordan, Syria, Lebanon, and Iraq invade, beginning the 1948 Arab-Israeli War.

December 11, 1948: The UN General Assembly passes Resolution 194, affirming the right of return for Palestinian refugees.

February – July 1949: Israel signs armistice agreements with Egypt, Lebanon, Jordan, and Syria, ending the war and establishing the “Green Line.”

Glossary of Terms

Al-Nakba: Arabic for “the catastrophe.” The term Palestinians use to describe the events of 1948, which resulted in their mass displacement and the loss of their homeland.

Armistice Agreements: A set of agreements signed in 1949 between Israel and its neighbours (Egypt, Lebanon, Jordan, and Syria) that formally ended the 1948 war and established demarcation lines (the Green Line).

British Mandate: The period from 1920 to 1948 when Britain administered Palestine under the authority of the League of Nations.

Green Line: The demarcation lines set out in the 1949 Armistice Agreements that served as Israel’s de facto borders until the 1967 Six-Day War.

Haganah: The main Zionist paramilitary organization during the British Mandate, which later became the core of the Israel Defense Forces (IDF).

Plan Dalet (Plan D): A military plan adopted by the Haganah in March 1948 to secure the territory for a Jewish state. Its implementation is a subject of intense historical debate regarding its defensive or offensive nature.

Right of Return: The political position and principle that Palestinian refugees, both those who fled or were expelled in 1948 and their descendants, have a right to return to their homes and properties in what is now Israel. Affirmed in UN Resolution 194.

UN Partition Plan (Resolution 181): A 1947 United Nations proposal to divide British-mandated Palestine into separate Arab and Jewish states, with Jerusalem under international control.

Zionism: A nationalist movement that emerged in the late 19th century advocating for the establishment of a homeland for the Jewish people in Palestine.

.

· South Asian Refugees: They were handled by the universalist UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) framework. Crucially, India and Pakistan, despite their poverty, framed the crisis as a domestic resettlement challenge. Refugees were granted citizenship and (however difficult) integrated into the national fabric. While trauma persisted, the legal question of return was closed. There is no “right of return” movement for Punjabi or Bengali refugees.

This discrepancy created what scholar Francesca Albanese calls a “political difference” in refugee status. South Asian refugees, however traumatized, became citizens of new nations. Palestinian refugees became, and remain, a statless people, their identity and grievance institutionalized by an international body.

Enduring Legacies: Frozen Conflicts and the Memory of Loss

The double displacement of 1947-48 did not end with the ceasefires. It built conflict into the DNA of the new states, creating legacies that are vividly alive today.

The National Identity of the Victors

· India and Pakistan were born in reciprocal trauma. Their national identities became defined in opposition to each other. This foundational hostility fueled three major wars, a nuclear arms race, and the persistent conflict over Kashmir—itself a monstrous offspring of partition’s flawed logic.

· Israel was founded on a demographic revolution, transforming a minority into a majority within its borders. Its identity as a Jewish state is inextricably linked to the negation of the Palestinian claim to the same land. The ongoing need to maintain a Jewish demographic majority continues to inform policies toward Palestinians on both sides of the Green LineGreen Line Full Description:The demarcation line set out in the Armistice Agreements following the war. It separated the State of Israel from the West Bank and Gaza Strip. For decades, it served as the de facto border, though it was never intended to be a permanent political boundary. The Green Line (named for the ink used on the map) represents the ceasefire positions of the opposing armies. It left Israel with significantly more territory than was originally proposed by the UN partition plan, while the remaining Palestinian territories fell under Jordanian and Egyptian administration.

Critical Perspective:The existence of the Green Line highlights the absence of a peace treaty. It created a physical and psychological partition of the land that divided families and severed economic ties. In the decades following the subsequent occupation of the West Bank, the line has been increasingly erased by settlement construction, rendering the prospect of a “two-state solution” based on these borders geopolitically impossible.

Further Reading

The End of the British Mandate: Imperial Withdrawal and the Onset of War

The UN Partition Plan of 1947: A Spark in a TinderboxThe 1948 War: Nakba and Independence

Plan Dalet: A Blueprint for Conflict

The Palestinian Nakba: A National Trauma

Arab States’ Intervention and the Widening War

The Palestinian Refugee Crisis

The 1949 Armistice Agreements: A Frozen Conflict

Israel’s Transformation: State-Building and Immigration

The Arab World After 1948: Political Upheaval

The Legacy of 1948: The Politics of Memory

.

The Politics of the Dispossessed

· For Palestinians, the Nakba is not a historical event but an ongoing process—”al-Nakba al-mustamirra”. The loss of 1948 is the core of national identity. The refugee camps in Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, and the occupied territories are not just homes but living monuments to the demand for return and justice. Events like the threat of eviction in Sheikh Jarrah in East Jerusalem are potent because they are seen as a continuation of the 1948 displacement, where Palestinians are denied property rights that Israeli law grants to Jews globally.

· For communities in South Asia, while a formal political “right of return” is absent, the memory of lost homelands—the watan in Pakistan for Indian Muslims, or ancestral villages in now-Pakistani Punjab for Sikhs and Hindus—persists in literature, film, and family lore. The border remains one of the world’s most militarized, and the trauma is transmitted epigenetically.

The Moral and Historiographical Battlefield

The struggle over the narrative of 1947-48 is as fierce as the political conflict. In Israel, the mainstream narrative long termed the war the “War of Independence,” portraying the refugee flight as a voluntary response to Arab leaders’ calls. The work of Israeli “New Historians” like Benny Morris, who accessed state archives, challenged this, detailing expulsions and massacres. In India and Pakistan, national histories often sanitize the violence, attributing it to “fanaticism” rather than political failure.

The Palestinian term “Nakba” (catastrophe) is itself a defiant act of historical framing, asserting a narrative of victimhood and injustice against the Israeli narrative of redemption and rebirth. In 2022, the UN began officially commemorating Nakba Day, a move Israel condemned as anti-Israeli—demonstrating how the battle over 1948’s meaning continues in international forums.

Conclusion: The Unfinished Partitions

The partitions of 1947-48 were catastrophic successes. They succeeded in creating new nation-states but failed to create peace or justice. They solved the British Empire’s problem of exit by transferring the catastrophic cost onto civilian populations.

The “double displacement” they engineered—first by violence, then by law—created two of the modern world’s most intractable problems. The legacy is a set of frozen conflicts where the past is never past: in the line of control in Kashmir, in the separation wall in the West Bank, in the rhetoric of politicians from Delhi to Islamabad and from Tel Aviv to Ramallah. These borders were drawn in haste and blood; they continue to bleed today.

The refugees of these twin cataclysms, and their descendants, are the living conscience of this unfinished history. Their ongoing plight is the clearest proof that partitions which prioritize political expediency over human dignity do not end conflicts; they merely re-found them on a basis of permanent grievance. In understanding 1947 and 1948, we are not studying ancient history. We are deciphering the origin code of some of the most dangerous and enduring crises of our present world.

Leave a Reply