The partition of British India in 1947 divided the subcontinent into two new states, India and Pakistan, along mainly religious lines. This violent break-up followed nearly a century of direct rule following the defeat of the 1857 uprising and rising communal tensions. Scholars stress that multiple, interlocking factors – political, religious, economic and social – drove Partition. None of these alone suffices, and historians continue to debate their relative importance. As Pandey and others note, we must “move beyond explanations of partition rooted simply in… long-standing Hindu-Muslim cultural difference or in images of a modernity that fixed borders and identities into bounded compartments” . This review surveys the literature on these causes, drawing on diverse perspectives (Indian, Pakistani, British) and a variety of interpretations.

Colonial Foundations and Early Politics (1857–1930)

The roots of Partition lie partly in colonial policies and the rise of nationalism. The Indian Rebellion of 1857 (the “Mutiny”) led Britain to transfer power from the East India Company to the Crown, inaugurating the Raj . Imperial administrators thereafter pursued a classic “divide and rule” strategy. As Shashi Tharoor observes, British India policy “fomented religious antagonisms” between Hindus and Muslims as a tool of colonial control . For example, in 1905 the viceroy Lord Curzon partitioned Bengal (east and west) explicitly to weaken anti-colonial militancy in that region and to win the support of the Muslim elite of East Bengal . (Two years later this decision was reversed, but it set a precedent of communal division.) The British also introduced communal electorates and separate legal codes, solidifying identity categories. When limited self-government arrived (Government of India Acts), Muslims and Hindus were often given separate representation. In Tharoor’s words, “when restricted franchise was grudgingly granted…, the British created separate communal electorates” that made religion a political boundary . Historians like Alastair Reid, Nirmal Bose and others show that these institutional measures sowed distrust. Official “census” categories, educational policies (e.g. separate schools), and coercive responses to dissent all contributed to a sense of difference. By the 1930s, as one scholar notes, British colonial arrangements had “invented the idea of Hindu and Muslim periods in Indian history,” giving the appearance that Indians were historically divided by religion .

At the same time, Indian nationalism was emerging. The Indian National CongressIndian National Congress The principal political party of the Indian independence movement. Founded in 1885, it sought to represent all Indians regardless of religion, leading the struggle against British rule under a secular, nationalist platform. The Indian National Congress was a broad coalition that utilized mass mobilization and civil disobedience to challenge the British Raj. Led by figures like Gandhi and Nehru, it advocated for a unified, democratic, and secular state. It consistently rejected the Two-Nation Theory, arguing that religion should not be the basis of nationality.

Critical Perspective:Despite its secular ideology, the Congress leadership was predominantly Hindu, and its cultural symbolism (often drawn from Hindu tradition) alienated many Muslims. Critics argue that the Congress’s refusal to form coalition governments with the League in 1937 was a strategic error that pushed the League toward separatism. Its inability to accommodate Muslim political anxieties within a federal framework ultimately contributed to the inevitability of Partition.

Read more (INC) was founded in 1885 on a broadly secular platform. In its early decades it campaigned for civil rights and later self-rule, bringing together Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs and others. Many Indian Muslims (including moderates like Jinnah at this time) initially supported joint nationalist causes . However, separate organizations also grew. The All-India Muslim League was formed in 1906 under British auspices (as Mukherjee points out, the League was the first of several “religion-based communal instruments” created or fostered by the British to weaken the nationalist movement ). Hindu communal organizations likewise arose – notably the Hindu Mahasabha (founded 1915) and later the RSS (1925) – which advocated a specifically Hindu identity and often opposed Congress. These groups tended to stand apart from the INC and disputed its claim to represent all Indians . In effect, by the 1920s and 30s politics in India was becoming bifurcated along communal lines.

Congress repeatedly insisted on a united India. From Congress’s standpoint, Partition was neither inevitable nor desirable. Congress leaders such as Gandhi and Nehru worked for Hindu–Muslim unity and decried sectarianism. Most Indian nationalists viewed the subcontinent as one country with multiple communities. As Indian historian Aditya Mukherjee emphasizes, Congress “tried the hardest to keep people together” and only accepted Partition when it seemed unavoidable . Indeed, many Muslim organizations (e.g. the Jamiat Ulema-e-Hind, Majlis-e-Ahrar, Hindu Mahasabha, Khudai Khidmatgar, Communist Party, Unionist Party of Punjab and others) explicitly opposed dividing India along religious lines . Even prominent Muslims like the Aga Khan III and many provincial Muslim League members initially envisaged a federal or united India . In a famous remark (later invoked by Mukherjee), Congress pointedly noted in 1947 that it was “unpatriotic” and “unnatural” to carve up India by religion .

Yet imperial policy and communalist currents gradually altered the frame. By the 1930s, the notion that Hindus and Muslims constituted separate “nations” gained purchase. In 1930 a resolution at the All-India Muslim Conference recognized a distinct Muslim political identity. The culmination was the Lahore ResolutionLahore Resolution Full Description:A landmark political statement adopted by the Muslim League in 1940. While it did not explicitly use the word “Pakistan,” it called for the creation of “independent states” for Muslims, serving as the formal point of departure for the separatist movement. The Lahore Resolution fundamentally changed the nature of the Indian political dialogue. It moved the Muslim League’s demand from constitutional safeguards within India to territorial sovereignty outside of it. It declared that no constitutional plan would be workable unless it recognized the Muslim-majority zones as independent entities.

Critical Perspective:Historians debate whether this was a final demand or a “bargaining chip” intended to secure a loose federation. The ambiguity of the text (referring to “states” in the plural) suggests that the final form of Pakistan was not yet decided. However, once the demand was made public, it galvanized the Muslim masses, creating a momentum that the leadership ultimately could not control, making compromise impossible.

Read more of March 1940, when the Muslim League demanded that “Muslim-majority areas” of northwestern and eastern India be grouped into “independent States” (Pakistan) . League leaders like Muhammad Ali Jinnah argued that India’s problem “is not of an inter-communal but manifestly of an international character,” implying that only separate sovereignty could resolve it . Jinnah himself said at times that he preferred a united or united–Bengal settlement, suggesting that Partition was a contingency rather than an ideological article of faith . But by 1940 the idea of Pakistan as a homeland for Indian Muslims was formally launched .

Political Factors and Leadership (1939–1947)

Political developments in the last years of British rule were decisive. World War II, Congress’s resistance to it, and the hurried transfer of power set the scene. After Britain declared India at war in 1939 without consulting Indian leaders, Congress ministries resigned en masse in protest. The British responded by co-opting the Muslim League into provincial governments and expanding its power, as Tharoor notes, to counter Congress and assume control . The 1945-46 elections reinforced communal polarization: the League won almost all Muslim seats, claiming to be sole spokesman for Indian Muslims. Congress refused to accept dividing power by religion, while the League pressed harder for Pakistan. In 1946 Jinnah called for “Direct Action” (mass protests) to force the issue. The resulting violence (e.g. the Calcutta Killings of August 1946) convinced many that civil war loomed. British viceroy Lord Mountbatten later recalled that Congress leaders felt “tired” of the bloodshed and saw Partition as a tragic “way out” .

Mountbatten’s plan rapidly ended British rule. In June 1947 he announced that the Raj would be partitioned – India into a Hindu-majority and a Muslim-majority state – on 15 August. This decision was influenced by the breakdown of talks (Cabinet Mission Plan of 1946 failed, Congress–League talks collapsed) and the British aim to exit quickly. British Prime Minister Attlee had vowed independence “at long last” and believed neither Congress nor the League alone could govern all India . Officially, Partition was presented as unavoidable due to “communal deadlock.” Mountbatten himself wrote in his diaries that Congress leaders opted for Partition when faced with “fires” of communal violence . Nevertheless, some historians argue that ultimate responsibility lies not just with Britain but with the Indian leadership. Talbot and Singh (2009) contend that the division was “contingent on a range of political choices made by both the British and India’s political elites” and in large measure “willed into existence [by Indian political leaders]” . In their view, Partition was not fully imposed by London but emerged from strategic decisions by Congress and League negotiators. This “revisionist” high‑politics interpretation contrasts with older views that saw Partition as an inevitable consequence of colonial rule or irreconcilable communities.

Religious and Communal Causes

Religion and identity played complex roles. By the 1940s political leaders cast communities in mutually antagonistic terms. The Muslim League’s two-nation theory held that Hindus and Muslims were distinct nations by faith and culture, incapable of joint democracy. As James Talboys Wheeler’s early followers or later League propagandists argued, Muslims would be “slaves” in a Hindu-majority India unless they had their own state. This idea had roots in earlier thinkers (Muhammad Iqbal, 1930) and was amplified by leaders’ rhetoric. League publications catalogued alleged injustices by Congress ministries (in jobs, budgets, etc.) to prove Muslim grievances . By 1946 League propaganda promoted the notion that only a separate Pakistan could safeguard Muslim interests. In his 1985 study The Sole Spokesman, Ayesha Jalal (a Pakistani-born historian) showed how Jinnah sought to fabricate a unified Muslim community on the basis of separate electorates and provincial interests. She emphasizes that the “Pakistan” demand was shaped as much by the colonial institutional context and League strategy as by “ancient” Hindu–Muslim antagonism . Jalal points out that Jinnah even accepted (temporarily) more moderate constitutional offers if they retained the possibility of Pakistan, indicating pragmatism rather than pure ideological fervor .

Hindu communalists supplied the other side. The Hindu Mahasabha and the RSS rejected the composite nationalist vision. They sometimes cooperated with the League (for example forming short-lived coalition governments in 1946 Punjab) and stoked fears of a Muslim takeover. Conversely, hard-line Hindus (and sections of Sikh leadership) feared Muslim domination in Pakistan and campaigned vocally against it. Notably, in Bengal and Punjab grassroots communal violence fed political narratives. Recent research (Adhijit Sarkar 2020) reveals that during the Bengal famine (1943–44), the Hindu Mahasabha exploited the crisis to stir communalismCommunalism Full Description:Communalism refers to the politicization of religious identity. In the context of the Raj, it was not an ancient hatred re-emerging, but a modern political phenomenon nurtured by the colonial state. By creating separate electorates and recognizing communities rather than individuals, the British administration institutionalized religious division. Critical Perspective:The rise of communalism distracted from the anti-colonial struggle against the British. It allowed political leaders to mobilize support through fear and exclusion, transforming religious difference into a zero-sum game for political power. This toxic dynamic culminated in the horrific inter-religious violence that accompanied Partition.: it accused Muslim administrators of “sabotage” and claimed Muslim failure to avert famine proved Pakistan’s economic “unviability” . Such incidents show how religion and economics intertwined: communal leaders on both sides blamed the other community for disasters and rallied support for separatist causes.

Scholars debate how deeply religion per se caused Partition. Some earlier accounts treated communal identities as primordial and inevitable. Others emphasize modern, political uses of religion. Pandey, for example, urges caution: “long-standing cultural and civilizational difference” cannot fully explain Partition without noting the late colonial context . Gyan Pandey argues that during the riots of 1946–47 it was not simply Indians versus the British, but Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs attacking one another . He highlights that Partition’s violence was unprecedented and must be understood in light of modern nationalist ideology and memory. In short, historians note that while Hindu–Muslim divisions existed before, they were intensified (or even partly created) by the politics of the 20th century – census categories, separate electorates, politicized religious revivalism – more than by any immutable “clash of civilizations.”

From the Pakistani perspective, Partition was often seen as the inevitable outcome of Muslim cultural nationalism. After independence, the dominant narrative in Pakistan portrayed Jinnah’s goal as a safe homeland for Indian Muslims, born of the Two‑Nation Theory. But Jalal (Pakistani scholar) and others remind us that Jinnah’s vision was originally more secular and pragmatic: he accepted compromises short of outright Partition, and even hoped for a united or independent Bengal . In her 1985 book The Sole Spokesman, Jalal argued that Jinnah viewed Pakistan as a bargaining chip and was not committed to a religious state per se. Nevertheless, by the mid-1940s he framed the conflict in international terms, insisting on separate sovereignty. Pakistani historians such as Ayesha Jalal or Talbot often emphasize British missteps but also the Agency of League leaders in “willing” Partition. Others (especially older Pakistani accounts) stress British betrayal or Congress reluctance to share power.

Economic and Social Factors

Economic distress and social change also contributed to the context of Partition. Colonial rule had transformed India’s economy and society, often unevenly. Deindustrialization in textiles and chronic agrarian crises (famines, land inequality) bred resentment in some areas. The Bengal famine of 1943Bengal Famine of 1943 Full Description:A man-made catastrophe that killed an estimated 3 million people in Bengal. Caused by British wartime policies—including grain exports and denial schemes—rather than food shortages, it severely destabilized the region on the eve of Partition. The Bengal Famine of 1943 was a devastating humanitarian disaster. The British administration prioritized feeding the army and the war effort over the civilian population. Inflation, hoarding, and the destruction of boats (to prevent Japanese invasion) destroyed the rural economy.

Critical Perspective:Critically, the famine was a “holocaust of neglect.” It exposed the utter callousness of the colonial state toward its subjects. Politically, it shattered social trust in Bengal. The desperate competition for resources heightened communal tensions, as political parties used the scarcity to mobilize support along religious lines, accusing rival communities of hoarding grain, which fuelled the violence that erupted during Partition.

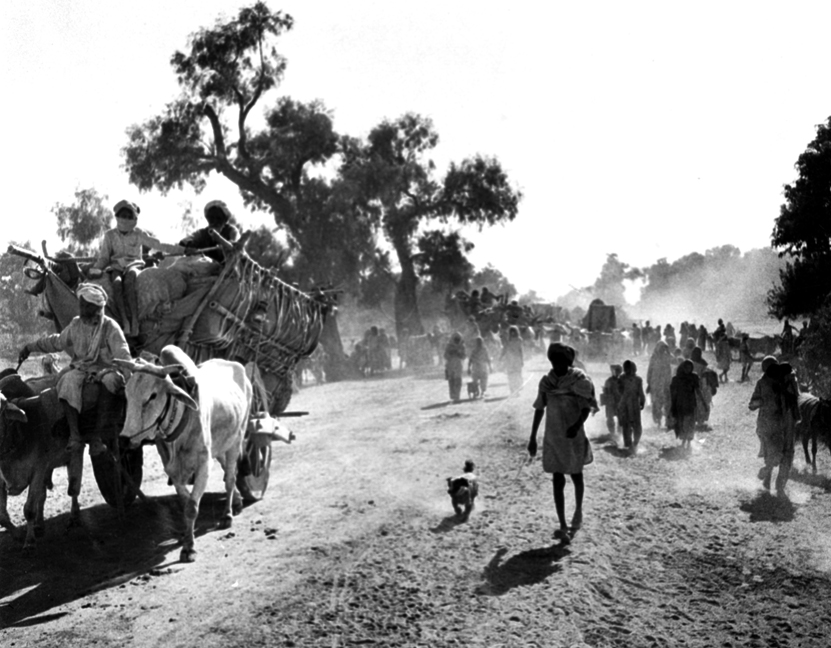

Read more–44 (caused by wartime policies and shortages) was a major trauma: an estimated 2–3 million died, and millions more were dislocated. As noted, the famine was used by political groups to score points: one important study shows the Hindu Mahasabha publicized the famine’s severity to argue that a Muslim-led province was economically unsustainable . (Interestingly, some counter-narratives accused Hindu groups of hoarding food for political ends.) In general, scholars of Partition’s social history (e.g. Mushirul Hasan, Ritu Menon, Urvashi Butalia) emphasize how peasant suffering, refugee movements, and communal violence interacted. Partition uprooted some 15–17 million people in sheer panic and left economic devastation on both sides. While it was not primarily fought over territory rich in resources, the economic context made people fearful of becoming minorities. For instance, many Muslims in mixed areas felt insecure about jobs and protection in a Hindu-dominated government, while many Hindus and Sikhs feared losing ancestral lands.

Socially, the British-introduced idea of religious majorities and minorities became self-fulfilling. By 1947, ordinary people had become conscious of their communal identity in new ways. The colonial census (since 1871) and electoral politics had repeatedly asked Indians to declare their religion first. Urban riots and communal propaganda spread through newspapers, strengthening group consciousness. The press, popular literature, and political oratory painted a picture of two competing communities clashing over the nation’s future. Against this backdrop, even a Congress leader lamented that none of his people would “remain alive” if Pakistan had been created earlier – a grim echo of the fears on all sides. Some historians argue that Partition was “an event of global significance, precisely because it was an event both of the biggest historical roots and roots in the distinctive uncertainties of this particular era” . In other words, it combined world-historical forces (decolonization, nationalism) with local political crises.

Historiographical Perspectives

Historians’ explanations of Partition have evolved. Early accounts (1950s–60s) often blamed “communalism” or cited leaders’ failings. Marxist historians looked at class and colonial exploitation as underlying factors. The so-called Cambridge School (Anil Seal, Ayesha Jalal) has highlighted the role of colonial institutions and elite negotiation, suggesting that Partition was not a “premeditated British conspiracy” but a byproduct of British withdrawal and elite bargaining. Jalal’s revisionist thesis in The Sole Spokesman argued that Jinnah’s insistence on Pakistan was initially flexible and that Congress leaders’ centralizing goals also led to a clash. Her critics (like Pandey, Mushirul Hasan) faulted her for “great man” focus, stressing popular communalism. Mushirul Hasan and others emphasize that Partition was both imposed from above and enacted from below: elite choices intersected with grassroots riots.

More recently, scholars have urged us to see Partition as part of longer historical processes. David Gilmartin (reviewing Partition historiography) argues that religion must be viewed in the larger “civilizational” and “cosmological” context of state-making – beyond simplistic communal categories . He suggests that Partition should be understood in terms of how new nation-states defined legitimate sovereignty amidst modern secular and religious ideas. Other historians (e.g. C.A. Bayly, Indrani Chatterjee) embed these events in even broader narratives of imperial networks and identity-making. In sum, the literature now recognizes that no single cause explains Partition. Both the colonial legacy of divided politics and the contingency of 1946–47 events mattered.

Indian and Pakistani historians sometimes offer different emphases. Indian scholarship (Mukherjee, Sarkar, Irfan Habib) tends to highlight British policy and Congress’s efforts for unity, often viewing Partition as a colonial “cut and run” after weakening Congress. Pakistani scholars (Talbot, Jalal, Ian Talbot in his Pakistan historiography) may stress Muslim agency and feelings of insecurity. British and Western historians (Newton, Wolpert) have alternately blamed British mismanagement or mutual mistrust. The truth, as this literature review shows, lies in a complex middle ground: Partition was neither the inevitable product of ancient hatreds nor a mere “imposition” by London. It emerged from a perfect storm of political impasse, communal mobilization, economic crisis, and departing empire.

Further Reading on the Deep Roots of Partition

Divide and Rule? — Details how colonial governance systematically fragmented Indian society.

The Bengal Famine and the Politics of Blame — Shows how economic crisis was used to stir communal mistrust.

Census, Community and Nation — Analyzes how imperial data practices entrenched religious categories

Leave a Reply to Mandates or Empire Repackaged? Susan Pedersen and the Complex Legacy of the Mandates System – Explaining History PodcastCancel reply