The Great Depression (1929–41) was the longest and deepest economic downturn in U.S. history. Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal (1933–39) introduced sweeping relief, recovery, and reform programs, but historians and economists still debate whether these reforms ended the Depression, merely eased its worst effects, or even prolonged it. This article examines the evidence on key New Deal policies. We review relief programs for the unemployed (CCC, WPA, PWA), financial reforms (Glass–Steagall, FDIC, SEC), and massive federal spending, and we engage with historiographical and economic debates (Keynesian vs. monetarist). Finally, we consider the New DealThe New Deal Full Description:A comprehensive series of programs, public work projects, financial reforms, and regulations enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. It represented a fundamental shift in the US government’s philosophy, moving from a passive observer to an active manager of the economy and social welfare. The New Deal was a response to the failure of the free market to self-correct. It created the modern welfare state through the “3 Rs”: Relief for the unemployed and poor, Recovery of the economy to normal levels, and Reform of the financial system to prevent a repeat depression. It introduced social security, labor rights, and massive infrastructure projects.

Critical Perspective:From a critical historical standpoint, the New Deal was not a socialist revolution, but a project to save capitalism from itself. By providing a safety net and creating jobs, the state successfully defused the revolutionary potential of the starving working class. It acknowledged that capitalism could not survive without state intervention to mitigate its inherent brutality and instability.

Read more’s long-term structural legacy (labor rights, infrastructure, the regulatory state). Throughout, we draw on recent peer-reviewed scholarship and primary sources to evaluate what really ended the Depression.

New Deal Relief and Jobs Programs

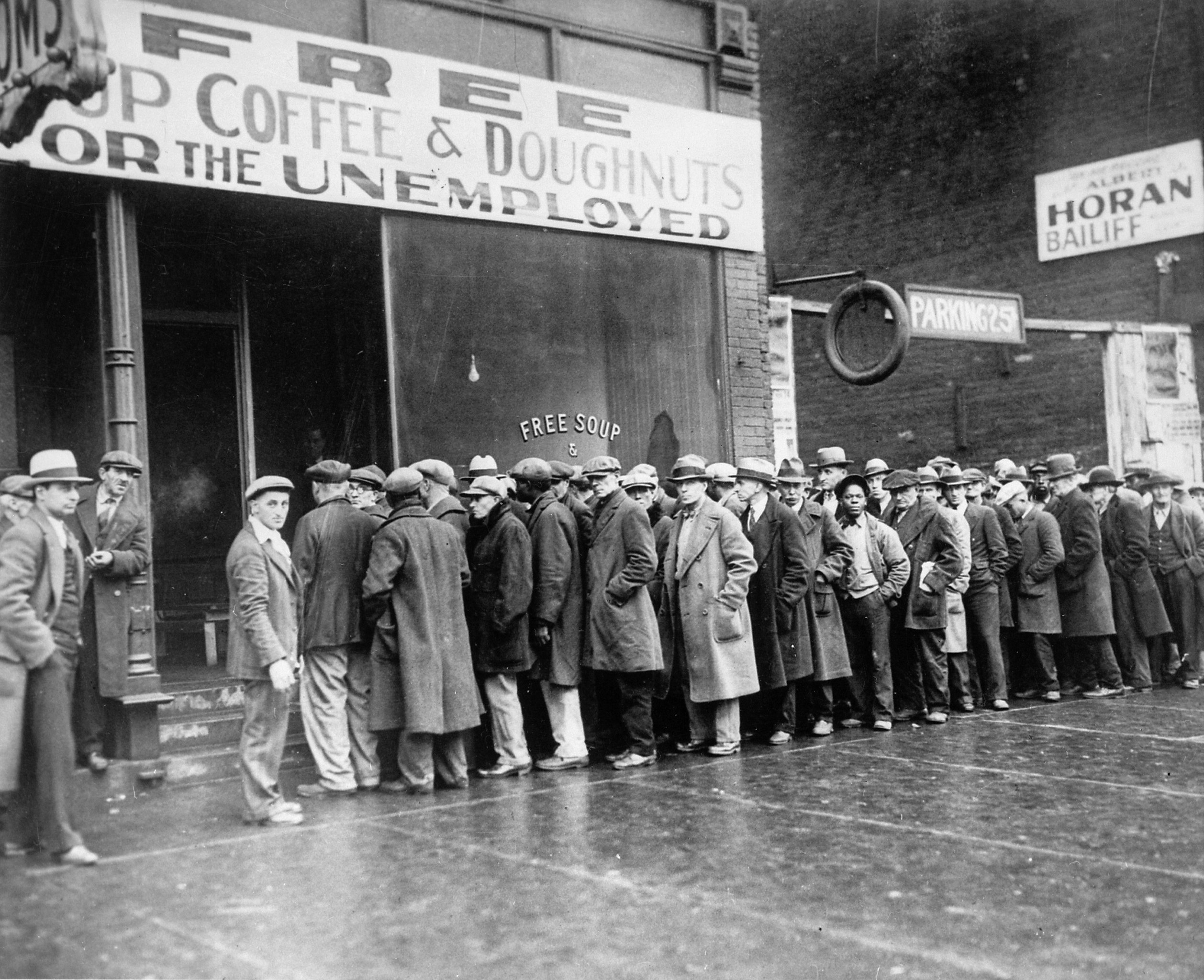

FDR famously promised the “forgotten man” relief through jobs. Early New Deal programs aimed to put millions of unemployed Americans to work on public projects. Three flagship relief agencies were the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), the Works Progress Administration (WPA), and the Public Works Administration (PWA).

Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC, 1933–42): The CCC employed young men (aged 18–25) on conservation projects in state and national parks. Typical CCC pay was $30/month (of which $25 was sent home), with work on reforestation, soil erosion control, and park construction. The CCC never enrolled more than about 300,000 men at a time . Modern research finds that CCC participation had long-term benefits for participants: a recent study using linked government records shows that longer CCC service significantly improved enrollees’ health, nutrition, and lifetime earnings, even if it did not raise their short-term wages or employment immediately after participation . In short, the CCC provided direct relief and vocational training, but its scale was too small to fully solve mass unemployment (which peaked near 25% in 1933). Works Progress Administration (WPA, 1935–43): The WPA was by far the largest New Deal jobs program. Under WPA chief Harry Hopkins, it put over 3 million workers to work in its first year . The WPA focused on labor-intensive construction and community projects. Roughly three-quarters of WPA jobs were in public works: over half of its employment involved highway, road, and street construction . Other major WPA projects included water and sewer systems, parks, public buildings (schools, libraries), and even cultural projects (murals, theater, and writing) though those were smaller in scale. The WPA stipulated that 90% of project budgets go to labor (to maximize jobs) . Its impact on unemployment was significant: by 1936 the WPA employed nearly 3 million workers each month. Infrastructure achievements were enormous – over its lifetime the WPA built or repaired an estimated 650,000 miles of roads (transforming rural and urban transportation) and thousands of bridges, schools, and other structures. (For example, it built New York’s first municipal airport – LaGuardia – and many civic buildings.) However, despite these gains, the economy never reached full employment in the 1930s. Some historians note that when WPA spending was cut back in 1937–38, unemployment rose again , suggesting that the program’s stimulus was real but insufficient to permanently end mass joblessness. Public Works Administration (PWA, 1933–39): The PWA, created by the National Industrial Recovery Act in 1933 and run by Interior Secretary Harold Ickes, funded large-scale engineering projects (dams, bridges, hospitals). PWA projects (e.g. Hoover Dam, Grand Coulee Dam) were capital-intensive and required long planning, so they spent money slowly at first. The PWA’s strength was building infrastructure, but historians note its direct impact on unemployment was smaller than the WPA’s because it moved fewer workers at one time. Nick Taylor observes that the PWA “had a far greater impact on the national infrastructure than on unemployment” in its early years . In sum, the major relief agencies provided immediate work and income to millions of Americans, built lasting public facilities, and revived hope – but by themselves did not fully restore full employment .

Taken together, New Deal relief programs did put millions to work and stoked some recovery. Estimates vary, but by 1937 unemployment fell from ~25% to around 14%. (Census data show industrial production up and unemployment down by mid-decade.) However, full employment was not reached until World War II. The New Deal provided crucial relief and kept people out of total destitution, but most scholars agree it did not, by itself, end the Depression .

| Dimension | Evidence of Success | Evidence of Limitation |

|---|---|---|

| Economic Recovery | GDP growth, banking stability | Persistent unemployment, 1937 recession |

| Political Stability | Democratic coalition dominance | Polarisation, court opposition |

| Social Welfare | Birth of social safety net | Exclusion of minorities and women |

| Long-Term Legacy | Permanent expectation of federal responsibility | Entrenched bureaucracy, uneven benefits |

Financial Reforms: Banking and Securities

A key New Deal goal was to stabilize the financial system after the collapse of 1930–33. Three landmark reforms reshaped banking and finance:

Glass–Steagall Banking Act (Banking Act of 1933): This law separated commercial banking from investment banking, to stop depositors’ funds from being used for stock speculations. It also gave the Federal Reserve tighter control over bank holding companies and required them to report regularly. Crucially, Glass–Steagall created the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) (through an amendment sponsored by Rep. Steagall) to insure bank deposits . As Julia Maues notes, Glass–Steagall was intended “to prevent the undue diversion of funds into speculative operations” by splitting banking functions . Larry Neal and Eugene White (2011) argue that Glass–Steagall’s separation of banking made deposit insurance feasible and helped restore faith in banks, even if it later limited small firms’ access to credit . In practice, Glass–Steagall and related oversight made U.S. banking safer. After deposit insurance began in January 1934, bank runs virtually ended. In 1934 only 9 banks failed nationwide, compared to over 9,000 bank closures in the preceding four years . In the words of the FDIC’s history, deposit insurance “was an immediate success in restoring public confidence and stability to the banking system” . In short, Glass–Steagall/FDIC helped bring banking under control and prevented future mass panics.

President Roosevelt signing the Banking Act of 1933 (Glass–Steagall) . This law created FDIC deposit insurance (implemented January 1934), which helped end bank runs. The FDIC reported only 9 bank failures in 1934 compared to over 9,000 in 1930–33 , showing the stabilizing effect of insurance.

FDIC (Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation): Created by Glass–Steagall, the FDIC guaranteed deposits (initially up to $2,500) starting in 1934. Its very existence eliminated the “panic” fear that had emptied banks in 1932–33. As one FDIC history notes, within months deposit insurance “restored public confidence and stability”: only nine insured bank failures occurred in 1934, versus thousands in prior years . By pooling risk among banks, the FDIC made runs on individual banks less likely and gave average citizens confidence that their savings were safe. This single reform dramatically stabilized the banking sector through the 1930s . Securities laws and the SEC (1933–34): Alongside banking fixes, FDR’s administration overhauled the stock market. The Securities Act of 1933 and the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 imposed new disclosure rules and created the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) as an independent regulator. The SEC was empowered to police exchanges and broker-dealers, require companies to file financial reports, and punish fraud. Joseph P. Kennedy became the first SEC chairman in 1934. While the SEC’s impact on ending the Depression is hard to quantify, contemporary accounts celebrated it as curbing the “excesses of the 1920s”. One account notes that the 1934 Act was “an attempt by FDR to get both private enterprise and the federal government working together to create a stronger, more equitable economy” by making markets “less hazardous” . In sum, the New Deal erected a new regulatory framework (bank separation, deposit insurance, market oversight) that stopped the financial system’s collapse and prevented recurrence of 1929–33 style crashes. These reforms are widely judged to have succeeded: as the Fed history observes, by the late 1930s the worst banking crisis in U.S. history “had not been repeated” thanks to these measures .

Fiscal Stimulus and Economic Recovery

Did New Deal spending stimulate a recovery in GDP and employment? Economists debate how much of the 1930s growth was due to FDR’s demand-side policies versus other forces (like monetary expansion or the eventual war build-up). Econometric work provides a clearer picture:

Christina Romer (1992), a leading economic historian, modeled the recovery from 1933 onward. She found that aggregate demand did rise in the mid-1930s, but the primary driver was monetary expansion – especially a huge inflow of gold (as European tensions rose) that massively increased the U.S. money supply. In Romer’s words, “nearly all the observed recovery of the U.S. economy prior to 1942 was due to monetary expansion”, and self-correction “played little role” . Indeed, U.S. real GDP (GNP) grew extremely fast: roughly +8% per year (1933–37) and +10% per year (1938–41) . These rates far exceeded what was seen even in normal booms. Without the monetary surge, Romer’s estimates imply output would have remained far lower. She concludes that FDR-era fiscal policy alone couldn’t have produced such gains; it was the expansion of the money stock (and later wartime spending) that “ended” the slump .

Keynesian economists, by contrast, emphasize government spending and deficit finance. John Maynard Keynes himself noted (in 1936) that deep depressions require public spending to absorb excess savings. Indeed, after mid-1937 the Roosevelt administration began running deficits (especially with Social Security and relief programs), and Keynesians credit this with helping stabilize output. However, even with New Deal spending, unemployment never fell below 14% before the war. A “Roosevelt Recession” hit in 1937–38 when the government actually cut back on spending and tightened monetary policy, causing a sharp GDP dip. This episode reinforced the Keynesian view that contracting fiscal stimulus can stall recovery.

Quantitatively, however, many studies (like Romer’s) find that New Deal deficits had a modest effect relative to monetary factors. Later analysis by Ahearn, Hansen, and others suggests that New Deal spending did raise local incomes and possibly reduced rural poverty (see Fishback et al.), but could not overcome a still-low national demand without external stimuli. In practice, only World War II defense spending (1941–45) finally achieved full employment: by 1941–42 the U.S. was back to 1920s output levels, but this was almost entirely due to war mobilization, not New Deal alone. As historian Gary Richardson notes, “return to full output and employment occurred during the Second World War” .

In summary, New Deal fiscal programs and relief boosted demand and GDP to some extent, but fell short of full recovery. Growth was impressive in the late ’30s, yet unemployment remained chronically high until the war. The consensus among economists is that Roosevelt’s spending underwrote an incomplete recovery – it was necessary to ease suffering, but the “multipliers” were low and deficit spending was too small and erratic to do the job without the gold inflow and wartime boom .

Historiographical Debates: Recovery, Prolongation or Preparation?

Scholars disagree on whether the New Deal prolonged the Depression or merely paved the way to recovery. A famous dissenting view by Cole and Ohanian (Chicago economists) argues that New Deal policies prolonged the slump. They point out that by 1939 output was still about 25% below pre-1929 trend (much deeper than a typical downturn), and real wages (set by union bargaining codes and relief programs) were about 20% above trend . In a general-equilibrium model they show that labor cartels (induced by NIRA and the Wagner Act) artificially raised wages, reducing employment. In their summary: “New Deal cartelization policies… limited labor competition and sustained high real wages, thus lengthening the depression.” . This view (echoing earlier critics) holds that interventions like minimum wages, collective-bargaining mandates, and subsidies to business often backfired.

By contrast, other historians emphasize the successes of reform. Many note that the New Deal saved capitalism by liberalizing union rights and creating social insurance. For example, the Wagner Act (1935) fundamentally reshaped labor relations. It outlawed “company unions”, guaranteed collective bargaining, and empowered the NLRB. As the FDR Library notes, union membership nearly tripled during the late 1930s – by 1940 around 9 million Americans were in unions . This new system arguably improved working conditions and wages (the Wagner Act is credited with ushering in a long boom of productivity and wage growth ). Similarly, Social Security (1935) introduced national unemployment insurance and pensions, which many credit with stabilizing incomes in the long run.

In the big picture, the New Deal did not end the Depression by late 1930s. Unemployment in 1939 was still about 15%, and by many accounts full recovery only came with WWII . In Roosevelt’s words, the nation “moved to war and eradicated unemployment” after 1941. Yet historians increasingly view the New Deal as necessary groundwork for the postwar economy: it rebuilt infrastructure, preserved democratic institutions, empowered labor, and created a regulatory framework that prevented future depressions (until 2008). As one modern consensus holds, the New Deal “failed to restore full prosperity but it prevented revolution, revived hope, and made the state a central player in the economy.”

Keynesian vs. Monetarist Interpretations

Economists’ interpretations split broadly along Keynesian versus monetarist lines.

Keynesian view: From a Keynesian perspective, the Depression was caused by inadequate aggregate demand, and ending it required sustained fiscal stimulus. Keynesians argue that the New Deal was only partly Keynesian. Early New Deal policy was cautious (Roosevelt even balanced budgets in 1936 and 1937), but after the 1937 downturn the administration embraced bigger deficits. Keynesians emphasize episodes like the 1937 fiscal “bust” (Roosevelt’s cutting of relief) as evidence that contractionary moves stalled recovery. They also credit programs (CCC, WPA, Social Security) with injecting demand. Notably, Keynes himself and his followers in the 1940s thought the New Deal’s spending was too limited; had FDR spent more aggressively (as in his 1940 plan), unemployment might have fallen faster. In this reading, the New Deal was a half-measure: valuable social reforms were enacted, but the core Keynesian cure of full counter-cyclical deficits wasn’t delivered until the war. Monetarist view: Monetarists (following Friedman & Schwartz) highlight money and financial factors. Milton Friedman famously blamed the Fed’s failures for the Depression. From this angle, FDR-era fiscal policies were secondary. Instead, monetarists stress the Fed’s mistakes: in 1928–29 the Fed raised interest rates to curb speculation, which suppressed U.S. and global demand . Then during the 1930–33 banking panics the Fed largely stood aside, failing to be a true lender of last resort . Only after Roosevelt’s 1933 bank holiday and reforms did the financial storm abate. In sum, the monetarist narrative asserts the Depression ended when the Fed and Treasury finally expanded the money supply (gold inflows, Treasury purchases). New Deal programs had little effect on output growth compared to monetary policy. This view was echoed by future Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke, who in 2002 praised Friedman and admitted “we did it” (the Fed’s failures) onstage at a Friedman tribute .

The truth likely incorporates both views: New Deal fiscal policy provided needed relief and some stimulus, but it was too inconsistent to rely on; monetary expansion (including going off the gold standardGold Standard Full Description:The Gold Standard was the prevailing international financial architecture prior to the crisis. It required nations to hold gold reserves equivalent to the currency in circulation. While intended to provide stability and trust in trade, it acted as a “golden fetter” during the downturn.

Critical Perspective:By tying the hands of policymakers, the Gold Standard turned a recession into a depression. It forced governments to implement austerity measures—cutting spending and raising interest rates—to protect their gold reserves, rather than helping the unemployed. It prioritized the assets of the wealthy creditors over the livelihoods of the working class, transmitting economic shockwaves globally as nations simultaneously contracted their money supplies. and war-driven base growth) did most of the heavy lifting for aggregate demand . Furthermore, non-monetary factors (banking stability, confidence) were critical. Many historians now agree that by late 1930s a consensus emerged: “monetary policy and external factors ended the slump, not the New Deal programs per se.” Nonetheless, Keynesian economicsKeynesian Economics Full Description:The dominant economic consensus of the post-war era which argued that the government had a duty to intervene in the economy to maintain full employment and manage demand. Neoliberalism defined itself primarily as a reaction against and a dismantling of this system. Keynesian Economics underpinned the “Golden Age” of capitalism and the welfare state. It operated on the belief that unregulated markets were prone to collapse and that the state must act as a counterbalance—spending money during recessions and taxing during booms—to ensure social stability and public welfare.

Critical Perspective:From the neoliberal viewpoint, Keynesianism was a slippery slope to totalitarianism. However, critics argue the dismantling of this consensus broke the social contract between capital and labor. By abandoning the commitment to full employment and social safety nets, the state abdicated its responsibility to its citizens, prioritizing the health of the currency over the health of the population.

Read more was born during the New Deal, and the era’s lessons (especially 1937) helped institutionalize counter-cyclical policy in later crises.

Long-Term Structural Legacy

The New Deal’s lasting impact is often measured not just in 1930s GDP, but in its enduring reforms and institutions. Three broad legacies stand out:

Labor rights and social policy: The National Labor Relations (Wagner) Act of 1935 established collective bargaining and union elections. Its effects were dramatic: union membership soared in the 1930s, from around 3.7 million in 1933 to roughly 9 million by 1940 . For decades unions became powerful players in manufacturing and industry, leading to the mid-20th-century “labor-management” accords. The Social Security Act of 1935 created unemployment insurance and old-age pensions (largely unfunded pay-as-you-go), forming the core of the modern welfare state. While not a jobs program, Social Security stabilized incomes for the elderly and poor, an institutional change still with us.

Infrastructure and public works: Beyond temporary relief, New Deal spending dramatically expanded U.S. infrastructure. The WPA and PWA built highways, dams (TVA, Hoover Dam), bridges, schools, airports and more. For example, a Federal Highway survey notes 650,000 miles of road were constructed or improved by the WPA . Many dams and power projects electrified rural America. While these projects had economic value in themselves, they also employed huge numbers and upgraded the nation’s capital stock. Eisenhower’s later interstate highways owe something to New Deal precedents.

Regulatory state: The New Deal vastly expanded federal oversight of the economy. It created or strengthened agencies to regulate finance (SEC, FDIC, Fed oversight), industry (NLRB), agriculture (AAA, albeit later gutted), housing (FHA), and more. These agencies endured long past 1940. Glass–Steagall’s bank separation lasted until 1999 and was credited (by some) with financial stability. The SEC made disclosure and fair play the norm in markets. In 1938 the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) introduced minimum wages and overtime, reshaping labor markets. These reforms meant that by 1940 the U.S. had a regulatory framework unseen before 1933. Many modern historians argue that these structural changes “refounded” capitalism in America, making it more durable.

| Phase | Dates | Character | Key Legislation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emergency Response | 1933–34 | Crisis management, bank reform, temporary relief | Emergency Banking Act, AAA, NRA |

| Institutional Reform | 1935–36 | Structural and welfare-based reform | Social Security Act, Wagner Act, WPA |

| Consolidation and Constraint | 1937–39 | Supreme Court backlash, recession, and conservative opposition | Judicial Reorganization Bill, Fair Labor Standards Act |

Conclusion

In summary, Roosevelt’s New Deal had mixed results in ending the Great Depression. Relief programs (CCC, WPA, PWA) undeniably put millions to work and built useful infrastructure, but unemployment stayed high into the late 1930s. Banking reforms (Glass–Steagall, FDIC, SEC) unquestionably stabilized finance and ended catastrophic bank runs. Monetary historians credit the final recovery mainly to inflationary money policy and the massive war economy, rather than to the New Deal’s budget deficits. Economists remain divided: Keynesians lament that fiscal stimulus was too limited, while monetarists highlight Fed failures and lingering regulatory drag.

Most scholars today conclude that the New Deal did not, by itself, end the Depression. Full economic recovery awaited World War II mobilization (which brought unemployment down to ~2%). Nevertheless, the New Deal’s importance lies in what it laid down: it saved capitalism from collapse by reforming its rules. It created the social safety net (Social Security, unemployment insurance), enshrined labor rights (Wagner Act, unions), and upgraded the national economy (roads, electrification). As FDR’s advisers hoped, these changes “provided confidence in the future” even when markets were still weak. In the words of one historian, the New Deal “did not resolve chronic unemployment, but it did revolutionize American life” .

Whether viewed as saviour or saint, the New Deal unquestionably shaped 20th-century America. The debate over its economic success—whether it ended or prolonged the Depression—will likely continue. But its enduring legacy in infrastructure, labor law, and financial regulation endures: for better or worse, we still live in the world its architects built .

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Keynesian Economics | The idea that governments should use fiscal policy—deficit spending and investment—to stimulate demand during economic downturns. |

| Priming the Pump | Roosevelt’s metaphor for public spending to revive private enterprise. |

| Deflationary Spiral | A cycle of falling prices, reduced wages, and lower consumption deepening economic crisis. |

| Institutional Reform | Structural changes to the American capitalist system—banking, securities, labour relations—to prevent future crises. |

| Political Realignment | The long-term shift in voter coalitions producing Democratic dominance from the 1930s to 1960s. |

| Second New Deal (1935–36) | The more radical phase of Roosevelt’s reforms focused on welfare and labour rights. |

Sources: Recent economic history research and archival analyses were used throughout. For unemployment and program effects see Aizer et al. (2022) on the CCC and Cole & Ohanian (1999) on labour and output . Financial reform data come from Federal Reserve and FDIC histories. Recovery narratives and growth figures draw on Romer (1992) and Fed publications. Labour outcomes and the Wagner Act are documented by the FDR Library. All interpretations are grounded in peer-reviewed economic history and contemporaneous sources as cited.

Leave a Reply