Introduction

The Great Depression was the most severe and prolonged economic crisis of the 20th century, lasting from 1929 through the late 1930s. It originated in the United States but quickly spread worldwide, leading to collapsing industrial output, mass unemployment, and social misery on an unprecedented scale . In the U.S., industrial production fell by over one-third and unemployment reached around 25% at its peak . Globally, no region was spared: what began as an American downturn soon “engulfed virtually every manufacturing country and all food and raw materials producers” as John Maynard Keynes observed in 1931 . Understanding why this catastrophe happened—and why it became so deep and long-lasting—requires examining a mix of long-term structural causes, short-term trigger events, and policy failures. It also demands a global perspective, since the Depression’s causes and effects were international in scope . This overview discusses the factors that led to the Great Depression, the collapse of global trade that followed, and how different historians and economists (Keynesian, monetarist, Marxist, and others) have interpreted the crisis over time. All interpretations agree on the Depression’s enormity; as Keynes rightly predicted, it proved to be a major turning point in economic history .

Long-Term Causes: The 1920s Economic Imbalances

Several deep-rooted imbalances in the 1920s set the stage for the Great Depression. In the aftermath of World War I, the global economy was left with significant financial vulnerabilities. European nations emerged from the war with heavy debts: Britain and France owed massive war loans to the United States, and Germany was saddled with reparations payments to the Allies . During the mid-1920s, this system was kept afloat by American lending. The United States had become the world’s leading international creditor, replacing Britain, and supplied roughly half of all international loans between 1924 and 1931 (about one-third of U.S. lending went to Germany) . This credit enabled Germany and others to pay war obligations and fuel growth, but it also created an unstable financial network that depended on continuous capital flows from the U.S. . By the late 1920s, U.S. lending abroad and foreign investment began to slow as American investors poured money into an overheated domestic stock market. The withdrawal of U.S. capital put strain on Europe’s debt-ridden economies, exposing the fragility of the postwar financial system.

At the same time, the international gold standardGold Standard Full Description:The Gold Standard was the prevailing international financial architecture prior to the crisis. It required nations to hold gold reserves equivalent to the currency in circulation. While intended to provide stability and trust in trade, it acted as a “golden fetter” during the downturn. Critical Perspective:By tying the hands of policymakers, the Gold Standard turned a recession into a depression. It forced governments to implement austerity measures—cutting spending and raising interest rates—to protect their gold reserves, rather than helping the unemployed. It prioritized the assets of the wealthy creditors over the livelihoods of the working class, transmitting economic shockwaves globally as nations simultaneously contracted their money supplies. of the 1920s imposed rigidity on national economies. In the rush to restore prewar monetary arrangements, many countries returned to the gold standard at misguided exchange rates . Several continental European nations (like France and Belgium) set their currencies at undervalued rates, which gave them a competitive export edge and led them to accumulate gold reserves . In contrast, Britain restored the pound to its pre-1914 gold parity in 1925 – an overvalued rate that made British exports expensive and uncompetitive . The UK then endured chronic high unemployment and relied on deflationDeflation Full Description:Deflation is the opposite of inflation and is often far more destructive in a depression. As demand collapses, prices fall. To maintain profit margins, businesses cut wages or fire workers, which further reduces demand, causing prices to fall even further. Critical Perspective:Deflation redistributes wealth from debtors (the working class, farmers, and small businesses) to creditors (banks and bondholders). Because the amount of money owed remains fixed while wages and prices drop, the “real” burden of debt becomes insurmountable. This dynamic trapped millions in poverty and led to the mass foreclosure of homes and farms. (forcing prices and wages down) to try to “restore competitiveness” under gold, a policy that proved painful and largely ineffective . Thus, by the late 1920s, global economic balances were skewed: gold was concentrated in countries like the U.S. and France, while debtor nations struggled . The international monetary system, meant to foster stability, instead transmitted strain from one country to another. As later scholars Barry Eichengreen and Peter Temin argue, this “gold-standard mentality” – the commitment to defend gold at all costs – constrained policymakers and helped turn what might have been a normal recession into a worldwide catastrophe . Governments felt bound to raise interest rates and cut spending to stay on gold, even when their economies faltered, which “sharply restricted the range of actions they were willing to contemplate” and “transformed a run-of-the-mill economic contraction into a Great Depression” .

Within the United States, the domestic economy of the 1920s (the “Roaring Twenties”) had underlying weaknesses masked by overall prosperity. Income inequality was high – wealth became concentrated among industrial and financial elites, while farmers and workers didn’t share evenly in the boom. Agricultural America, in particular, suffered from low prices and overproduction throughout the 1920s, which depressed farm incomes. Industries like coal mining and textiles also struggled even before 1929. Meanwhile, the rapid growth in productivity and output during this decade outpaced wage growth, contributing to underconsumption: ordinary households’ purchasing power did not keep up with the economy’s capacity to produce goods . Easy credit and new consumer finance masked this gap for a time (many Americans bought cars and appliances on installment plans), but it meant the economic expansion rested on a shaky foundation of debt. Business investment in new factories also began to slow by the end of the decade as markets became saturated . In essence, overproduction and overinvestment loomed – a point that some contemporary observers noted. (Industrialists like Henry Ford and Edward Filene warned of “overproduction” and “underconsumption” problems, fearing the economy was producing more than people could afford to buy .) These imbalances implied that the spectacular growth of the 1920s was vulnerable if any major shock undermined confidence or spending.

Short-Term Triggers of the Crisis (1929–1931)

The Great Depression is often dated to the dramatic stock market crash of October 1929, which punctured the speculative bubble on Wall Street. Share prices had soared to extreme heights in the late 1920s, and when confidence faltered in autumn 1929, the market collapsed. The crash destroyed a great deal of paper wealth, badly shaken investor and consumer confidence, and marked the abrupt end of the Roaring Twenties expansion . However, the stock market crash was just one trigger and did not immediately cause the full Depression by itself. Its true significance lay in how it exposed and exacerbated the economy’s underlying weaknesses. After the crash, spending by businesses and consumers dropped as uncertainty grew. Industrial production and employment began to decline in late 1929, signaling the start of a recession.

More damaging were the financial crises that followed in the early 1930s. In the United States, a wave of banking panics swept the country. Many banks had lent heavily during the 1920s boom and now faced loan defaults and withdrawals. Lacking deposit insurance or a strong lender of last resort, small banks began failing by the hundreds. Regional banking panics erupted in late 1930 and again in 1931 as fearful depositors pulled out funds . Each panic further contracted the money supply and credit availability, causing monetary contraction that choked the economy. The cumulative effect was devastating: from 1929 to 1933, approximately one-third of all U.S. banks collapsed, and the nation’s money stock fell by about the same proportion . According to Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz’s influential monetarist study, the “great contraction” of the money supply turned what might have been an ordinary downturn into a relentless spiral of falling prices and output . With fewer banks and less money in circulation, consumer spending and business investment plunged, reinforcing the downturn . By March 1933, the U.S. banking system had effectively disintegrated – President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s first act was to declare a national bank holiday to halt the panic and reorganize banks .

Internationally, financial contagion spread as well. In May 1931, the failure of a major Austrian bank (Credit-Anstalt) triggered a broader banking crisis in Central Europe. Soon banks in Germany and other countries came under pressure. These crises led investors to pull capital out of weaker economies and seek the safety of gold or U.S. dollars. The international financial system began to unravel in 1931: Britain was forced to abandon the gold standard in September 1931, after speculative attacks on the pound depleted its gold reserves . Dozens of countries followed Britain in leaving gold over the next year. But in the frantic months before they left gold, many nations dramatically tightened monetary policy to try to defend their currencies’ gold parity – effectively raising interest rates in the middle of a depression, which made their recessions even worse . For example, the U.S. Federal Reserve, faced with gold outflows after Britain’s departure, hiked interest rates in late 1931 to try to keep gold from leaving the U.S. . This move, as one historian noted, was “the exact reverse of” what the domestic economy needed and “little wonder” it further weakened an already collapsing banking system . Thus, short-term crises between 1929 and 1931 – the market crash, successive bank panics, and currency crises – interacted disastrously with the long-term vulnerabilities. By late 1931, the world economy was in freefall, with no effective coordinated response yet in place.

Structural Factors and Policy Mistakes

Beyond the immediate triggers, several structural economic and political factors explain why the downturn was so deep and protracted. A critical factor was the policy response – or lack thereof – by governments and central banks in the early 1930s. In hindsight, policymakers made major mistakes that either caused the slump to worsen or failed to mitigate it. One of the most significant was the adherence to the gold standard, which has been widely identified by economic historians as a core mechanism that transmitted and magnified the Depression globally . Because currencies were tied to gold, central banks felt compelled to prioritize defending their gold reserves over domestic economic stimulus. When faced with banking crises or recession, the “orthodox” gold-standard playbook demanded raising interest rates and contracting credit to stem gold outflows . These deflationary measures were precisely the opposite of what was needed to fight the economic downturn. Modern analysis strongly supports the view that “adherence to the gold standard caused the Depression, [and] abandoning gold started recovery”, as economist Peter Temin succinctly argues . Countries that freed themselves from the “shackles of gold” earlier gained policy flexibility and tended to recover sooner, whereas those that stayed on gold suffered longer .

In the United States, the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy failures were pivotal. Rather than aggressively easing credit once the economy contracted, the Fed initially tightened. It had raised interest rates in 1928–29 to curb stock speculation, a move that helped prick the bubble but also “slowed economic activity” domestically . Worse, because of the gold-standard links, the Fed’s rate hikes “triggered recessions in nations around the globe” as other countries raised rates to maintain gold parity . When banking panics struck from 1930 onward, Fed officials disagreed on how to respond. Some held a “liquidationist” view – exemplified by U.S. Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon’s infamous advice to “liquidate labor, liquidate stocks, liquidate farmers” to purge bad investments – believing that allowing banks and businesses to fail was a harsh but necessary cleansing of the economy . This mindset, influenced by the real bills doctrine, led the Fed to stand aside as banks collapsed, instead of vigorously acting as lender of last resort . The result was a drastic contraction of the money supply and a wave of deflation: between 1930 and 1933, the U.S. money stock shrank about 30%, and prices fell by a similar magnitude . Deflation had pernicious effects – it increased the real burden of debt on farmers and homeowners, further discouraged new investments (since falling prices meant any new project would yield lower revenues), and led to more bankruptcies . In the words of Ben Bernanke (a leading scholar of the Depression and former Federal Reserve chairman), the Fed’s missteps turned the episode into the “worst economic disaster in American history”, a verdict he summarized with the frank admission: “We did it… we won’t do it again.” .

Another structural factor was the lack of international economic cooperation. The late 1920s and early 1930s were marked by a failure of collective leadership in the global economy. Historically, Britain had been the preeminent financial stabilizer (the lender of last resort to other countries) in prior crises, but by 1930 Britain was overextended and no longer able to play that role. The United States, now the leading economic power, was reluctant to assume responsibility for global stability. Economic historian Charles Kindleberger famously argued that the Depression was exacerbated by the absence of a hegemonic power to coordinate actions – “no longer London, not yet New York” as the locus of leadership . In practical terms, this meant there was no one to organize support for countries in trouble or to resist the spread of protectionismProtectionism Full Description:Protectionism involves the erection of trade barriers ostensibly to “protect” domestic industries from foreign competition. As the global economy contracted, nations panicked and raised tariffs to historically high levels in a desperate attempt to save local jobs. Critical Perspective:This created a “beggar-thy-neighbor” cycle of retaliation. When one dominant economy raised tariffs, others followed suit, causing international trade to grind to a halt. Instead of saving industries, it choked off markets for exports, deepening the crisis. It illustrates how the lack of international cooperation and the pursuit of narrow national interests can exacerbate a systemic global failure., discussed below. International conferences and attempts at cooperation (such as the 1933 World Economic Conference) achieved little, as nations prioritized their own narrow interests amid the crisis. This leadership vacuum and policy disarray allowed the downturn to feed on itself across borders.

Collapse of Global Trade and the Spread of Protectionism

One of the most dramatic aspects of the Great Depression was the collapse of global trade. As demand and production plummeted, world commerce contracted sharply. Between 1929 and 1933, the value of world trade fell by roughly two-thirds, an astonishing drop that far outpaced the decline in global output . Several forces drove this trade implosion. First, the Depression itself reduced incomes and import demand worldwide – a “sharp contraction in income and demand” meant countries simply bought and sold far fewer goods internationally . World prices were falling (deflation), which also shrank the nominal value of trade. But crucially, new trade barriers and protectionist policies compounded the decline. In 1930, the United States passed the Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act, which steeply raised U.S. import duties on thousands of products. Smoot–Hawley was intended to protect American industries and farmers from foreign competition, but in practice it backfired: U.S. trading partners retaliated with their own tariff hikes and import quotas . As one account notes, President Hoover’s failure to veto Smoot–Hawley led to higher tariffs globally and “ultimately led to retaliatory action” abroad . Protectionist measures proliferated around the world in the early 1930s. Countries imposed not only tariffs but also import quotas, exchange controls, and bilateral trade agreements that diverted commerce into narrow channels . The era saw a fragmentation of the world economy into trade blocs – for instance, the British Empire turned inward with “Imperial Preference” tariffs after 1932, and other nations forged regional or colonial arrangements to shield themselves.

The quantitative impact of these policies was severe. By 1932, U.S. exports had fallen to about one-third of their 1929 level in dollar terms . Across the major economies, exports and imports dropped even more steeply than output: for advanced countries, real GDP fell about 16% from 1929 to 1932, but import volumes fell by over 23% in the same period . This indicates that world trade contraction was not just a passive result of the Depression but also an active driver that “deepened the Great Depression” . For countries reliant on exporting primary commodities (such as many in Latin America, Southeast Asia, and Africa), the collapse of export revenues was devastating, transmitting the Depression to corners of the globe far from Wall Street. For example, prices of commodities like wheat, cotton, and rubber hit record lows, bankrupting farmers and plantation owners and forcing many debtor nations to default on loans. Some economists note that falling global demand was the primary cause of trade collapse, with protectionism making a secondary (but still harmful) contribution . Indeed, even had tariffs not risen, trade would have shrunk due to the Depression’s deflation and output collapse. But the beggar-thy-neighbor trade policies unquestionably exacerbated the crisis by undermining international economic linkages just when they were most needed. They also fueled political tensions: the retreat into economic nationalism hindered international cooperation and fostered resentment among nations, which had ominous implications for the decade’s geopolitics.

Comparative National Experiences and Global Impact

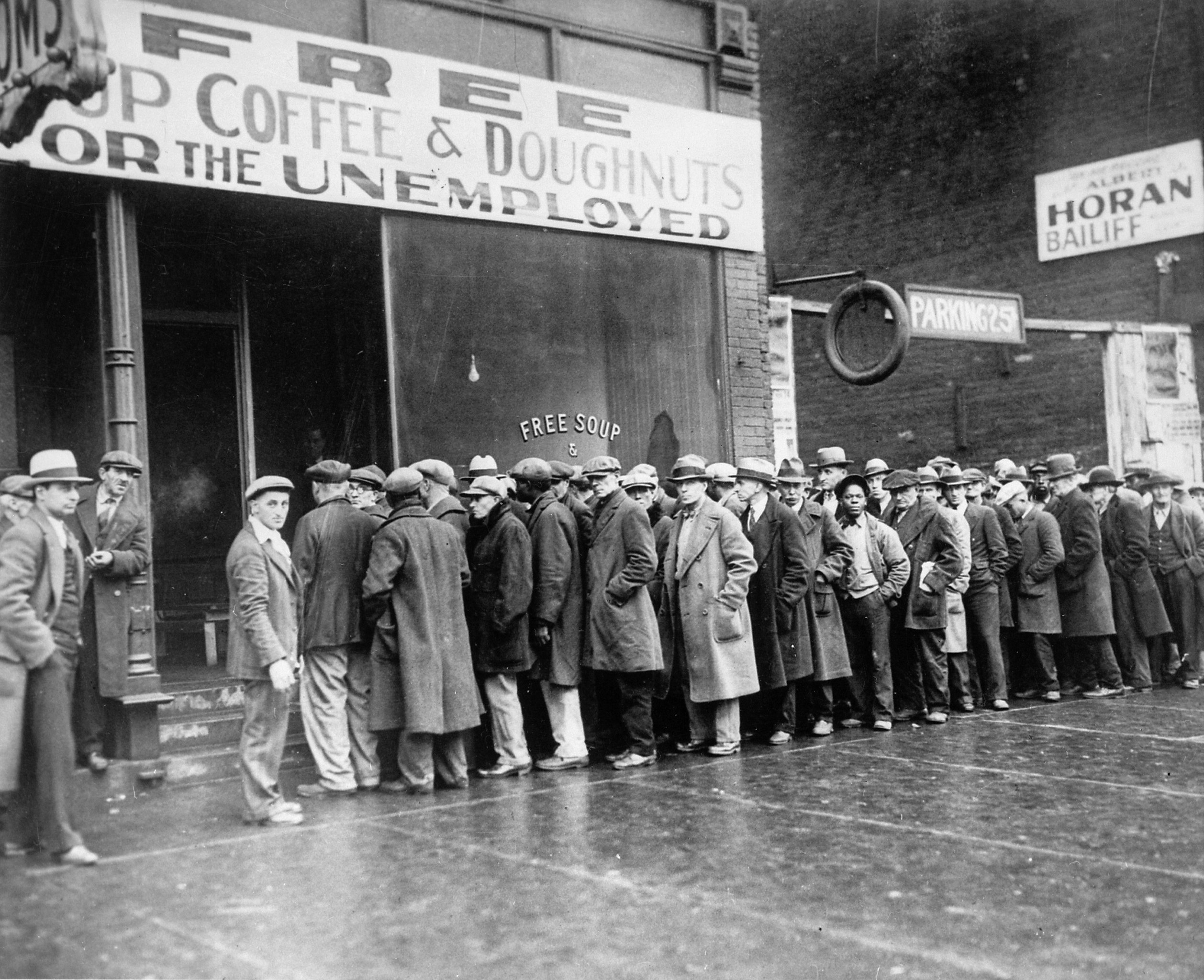

Although the Great Depression was a global phenomenon, national experiences varied in timing, depth, and recovery, often depending on policy choices and economic structures. In the United States, where the crisis began, industrial output fell by nearly half and unemployment reached around 25% by 1933. The U.S. saw a fragile recovery after 1933 with the New Deal reforms, but full employment was only restored by the mobilization for World War II . Germany, similarly, was hit extremely hard: by 1932 its industrial production had been cut roughly in half and unemployment also hit 20–30%. The German banking system crashed in 1931, and the Weimar government’s adherence to austerity (cutting spending to balance budgets) only worsened the downturn. This economic agony was a key factor in the rise of Adolf Hitler’s Nazi movement by 1933. Notably, once in power, the Nazi regime implemented massive public works and rearmament programs that eliminated unemployment faster than any democracy’s efforts – but at the cost of preparing for war.

Britain experienced a less dramatic contraction than the U.S. or Germany, partly because it had been in a slow grind of high unemployment through much of the 1920s (so the boom and bust were less pronounced). British industrial production fell perhaps 10–20% and unemployment peaked around 15%. Crucially, Britain left the gold standard in September 1931, which gave it monetary breathing room. Freed from gold, Britain eased credit conditions (“cheap money”) and the pound’s devaluation boosted exports a bit . These steps helped Britain start recovering by late 1932 – earlier than the gold-bloc countries that stayed on gold. Indeed, evidence shows that, across the world, the earlier a country abandoned the gold standard, the shallower its downturn and the sooner recovery began . Countries like Britain, Scandinavia, and Japan, which all left gold in 1931, generally bottomed out and resumed growth by 1933. In contrast, France, Belgium, and others remained on the gold standard until 1935–36 (the so-called “Gold Bloc”). These nations endured prolonged deflation and high unemployment well after other economies had started to heal. France, for example, didn’t begin a robust recovery until it finally devalued the franc in 1936.

Meanwhile, many primary-producer and colonial economies faced a different pattern. Nations in Latin America (Brazil, Argentina, etc.) and parts of the British Empire (Australia, India, etc.) were hit initially by collapsing commodity prices and export revenues. But some of these countries took unorthodox measures – for instance, many Latin American governments abandoned the gold standard, defaulted on foreign debts, and adopted import-substitution industrialization policies. This helped cushion their economies after the initial shock. By the mid-1930s, countries like Argentina and Brazil were seeing recovery through domestic manufacturing growth behind protective barriers, even as international trade remained anemic. The Soviet Union, interestingly, was insulated from the capitalist world’s crisis (having a planned economy); it continued its First Five-Year Plan industrialization amid the global depression, a fact that did not go unnoticed by contemporary observers.

In summary, while the Great Depression was global, the degree of suffering and the path to recovery differed. A key determinant was policy: nations that avoided the worst policy errors (such as early currency devaluation, bank rescue measures, or fiscal stimulus) tended to fare better than those that adhered to rigid orthodoxy or imposed austerity. The collapse of global trade meant export-dependent economies suffered gravely, but it also compelled some to develop domestic industries. These varied experiences later informed economists and policymakers in crafting post-World War II institutions (like the International Monetary Fund and World Bank) aimed at preventing such a collapse of global economic cooperation from happening again.

Historiographical Debates and Interpretations

The Great Depression has been a fertile ground for economic historians and has given rise to major schools of thought about its causes and lessons. Over time, interpretations have evolved, reflecting both new evidence and the changing economic ideologies of later eras. Here we outline the key historiographical debates and the perspectives of the principal schools: Keynesian, monetarist, Marxist, and others.

Keynesian Explanation (Demand-Driven Collapse)

The Keynesian interpretation, named after British economist John Maynard Keynes, emphasizes a collapse in aggregate demand – in other words, a massive decline in spending by consumers, businesses, and governments. Keynes himself, writing in the early 1930s and in The General Theory (1936), argued that the Depression stemmed from a fundamental failure of demand: after the 1929 crash, investment spending fell sharply and consumers curtailed expenditures, creating a self-reinforcing downward spiral. With prices and wages falling (deflation), real interest rates stayed high and businesses found little reason to invest, while unemployed workers had little money to spend – a classic underconsumption problem . In Keynes’s analysis, there was no automatic mechanism in unregulated markets to ensure a recovery; on the contrary, the economy could settle into an equilibrium with high unemployment. The Keynesian remedy was active government intervention: fiscal stimulus (such as public works and deficit spending) to prop up demand, and accommodative monetary policy, rather than austerity. Keynes famously quipped that during slumps, governments might even do well to pay people to dig holes and fill them up again – anything to inject purchasing power and break the cycle of decline. In fact, Keynesians see the Depression as proof that laissez-faire policies failed, and that only vigorous government action (ultimately wartime spending in the late 1930s) ended the slump .

Historically, for decades after World War II, the Keynesian interpretation dominated both economics textbooks and policy circles. The Depression became a cautionary tale that justified the new postwar consensus in favor of demand management: governments accepted responsibility for maintaining full employment through fiscal and monetary tools. As one summary notes, by the mid-20th century “the Keynesian explanation of the Great Depression was increasingly accepted by economists, historians, and politicians” . The narrative was straightforward: a collapse of private demand caused the Depression, and expansionary government policy was the solution. This view informed the U.S. New Deal as well (though Keynes’s influence on New Deal policies was indirect, since many New Deal measures were conceived before The General Theory). Even so, it’s worth noting that Keynesian historians also study structural reasons for the demand collapse – for example, the inequality and overproduction issues of the 1920s that left insufficient mass demand to buy what factories produced. Overall, the Keynesian school frames the Depression primarily as a failure of aggregate demand and a case where markets did not self-correct, requiring public intervention.

Monetarist Explanation (Monetary Collapse and Policy Failure)

The Monetarist interpretation, championed by Milton Friedman and Anna J. Schwartz, shifts the focus from real demand to monetary forces. In their influential work A Monetary History of the United States (1963), Friedman and Schwartz contend that the Great Depression was caused (or at least gravely worsened) by a drastic contraction of the money supply and the Federal Reserve’s failure to prevent banking collapses . They documented that from 1929 to 1933, the U.S. money stock fell by about one-third – a stunning shrinkage that they dubbed “the Great Contraction.” According to monetarists, this monetary implosion led to deflation and a collapse in nominal incomes, which in turn drove the economy into depression. Crucially, Friedman and Schwartz argue that the Federal Reserve could have and should have acted to counter this – for example, by aggressively lending to banks in panic (lender of last resort) or by open-market operations to increase the money supply. The Fed’s passivity and errors (such as raising interest rates at the wrong time and failing to rescue banks) are blamed for turning an ordinary recession into the Great Depression . In Friedman’s words, the Fed “transformed what might have been a garden-variety recession into a deep and lasting depression” through its mistakes . Monetarists do not necessarily deny that other factors (like overinvestment or demand shocks) played a role, but they assert those were secondary. The prime mover was monetary: a decline in the money supply leading to a decline in spending (since people hoarded cash in fear) .

This view gained prominence in the 1960s as a challenge to the Keynesian consensus, and by the 1980s many mainstream economists had incorporated the monetarist lessons. Notably, Ben Bernanke’s research built on monetarismMonetarism Monetarism is the economic school of thought associated with Milton Friedman, which rose to dominance as a counter to Keynesian economics. It posits that inflation is always a monetary phenomenon and that the government’s role should be limited to managing the currency rather than stimulating demand. Key Mechanisms: Inflation Targeting: Using interest rates to keep inflation low, even if high interest rates cause recession or unemployment. Fiscal Restraint: Opposing government deficit spending to boost the economy during downturns. Critical Perspective:Critics argue that monetarism breaks the post-war social contract. By prioritizing “sound money” and low inflation above all else, monetarist policies often induce deliberately high unemployment to discipline the labor force and suppress wages. It represents a technical solution to political problems, removing economic policy from democratic accountability. by examining how bank failures hurt the economy not just by shrinking money, but also by disrupting credit allocation – what he called “non-monetary effects” of the financial crisis on output . The monetarist emphasis is on avoiding central bank blunders: it implies that if the Fed (and other central banks) had acted more decisively – for instance, like the Fed did in later crises by cutting rates and providing liquidity – the Depression could have been much less severe or even largely prevented. This debate had real policy consequences: it informed central bankers’ responses to the 2008 financial crisis, for example, where Bernanke (deeply aware of 1930s mistakes) made sure to flood the system with liquidity to avoid another “great contraction.” Monetarists essentially reinterpret the Great Depression as a tragic failure of monetary policy, rather than an inherent flaw of capitalism or aggregate demand per se . Their work doesn’t necessarily oppose Keynesian remedies (they acknowledge fiscal stimulus can help once rates are at zero), but it prioritizes stable money growth and banking stability as the keys to avoiding depressions.

Marxist Perspective (Crisis of Capitalist Overaccumulation)

From a Marxist or radical perspective, the Great Depression is viewed not as a policy accident but as a manifestation of deep structural contradictions in the capitalist system. Marxist economists interpret the Depression as a classic crisis of overaccumulation: during the 1920s, capitalists accumulated productive capacity and capital far beyond what could be profitably invested or sold, given the limits of workers’ purchasing power . In this view, capitalist economies are inherently prone to periodic crises because of the tendency for the rate of profit to fall and for production to outrun demand (since wages are kept relatively low). By the late 1920s, according to this theory, the system had built up enormous productive potential (factories, machinery, etc.) but the masses were too impoverished to consume the output – leading to classic overproduction and inventories glutting the market. The resulting collapse was therefore “inevitable” in a sense, as part of capitalism’s boom-bust cycle . Marxist analyses often highlight how the Depression validated Marx’s 19th-century predictions about the instability of capitalism: the severity and duration of the 1930s slump were seen as proof of an intrinsic systemic failure . Influential Marxist scholars like Paul Sweezy and Ernest Mandel later argued that monopoly capitalism and imperialist expansions only delayed but could not prevent such crises. They also pointed out factors like stagnating profit rates, financial speculation, and inequality as contributing to the collapse. A Marxist lens might also note how the Depression led to social and political upheaval (e.g. the growth of communist and socialist movements, and ultimately World War II) as capitalism sought to overcome its crisis through war and destruction of excess capacity.

While the Marxist interpretation was widely held among leftist intellectuals during the 1930s and 1940s (many saw the Depression as proof of capitalism’s failure), it has been less influential in mainstream academic economics since the mid-20th century . Nonetheless, it remains an important part of the historiography. It reminds us that issues of class inequality, overproduction, and the profit motive are vital to understanding why the pre-1929 boom was unsustainable. It also underscores that the Great Depression was not merely a result of bad policy or random shock, but had roots in the dynamics of the capitalist system itself. In recent decades, some Marxian-inspired analyses have revisited the period, comparing the 1930s to modern episodes of financial crisis and “secular stagnation,” often arguing that without fundamental reforms, capitalism is prone to repeat such calamities.

Other Interpretations (Austrian School and Beyond)

In addition to the above major schools, other interpretations of the Great Depression have contributed to the debate. One noteworthy perspective comes from the Austrian School of economics (thinkers like Friedrich von Hayek and Ludwig von Mises). The Austrian view holds that the Depression was the consequence of an unsustainable boom fueled by cheap credit and misallocation of resources in the 1920s. According to Hayek and others, central banks (notably the U.S. Fed) kept interest rates too low and allowed credit to expand excessively during the mid-1920s, which fed speculative bubbles (in stocks, real estate, etc.) and overinvestment in capital goods. When the credit boom inevitably ended, the economy faced a necessary “liquidation” of bad investments. From this angle, the Depression was a painful but ultimately cleansing process, as the market purged itself of malinvestments. Austrians tend to argue that government efforts to prop up wages or bail out failing firms (including some New Deal policies) actually prolonged the agony by preventing the market from adjusting prices and resources quickly. For example, Andrew Mellon’s liquidationist stance reflects this thinking: allow bankruptcies and deflation to run their course, so that the economy can reset (Mellon believed this would “purge the rottenness out of the system”) . The Austrian interpretation is in stark opposition to the Keynesian – Austrians believe the cure lies in laissez-faire and not interfering with the contraction, whereas Keynesians advocate intervention to shorten the downturn. While the Austrian school’s explanation has not been as influential in academic literature, it has had a lasting political influence in arguments against government intervention.

Another contribution to understanding the Depression came from Irving Fisher’s “debt-deflation” theory (1933). Fisher, a prominent American economist, argued that the combination of excessive debt and deflation was key. When prices fall, the real value of debt actually increases, so borrowers become more burdened even as their incomes drop – leading to more defaults and a vicious cycle. This debt-deflation spiral was indeed evident: deflation in the early 1930s dramatically raised the real debt of farmers, homeowners, and businesses, intensifying bankruptcies and bank failures. Fisher’s insight was somewhat forgotten for decades but later integrated into modern explanations (and echoes of it appeared in Bernanke’s work on credit collapse).

Modern economic research has also introduced “real business cycle” or supply-side considerations. For example, some economists (Cole and Ohanian, 2004) have controversially argued that certain New Deal policies which tried to raise wages and restrict competition (like the National Industrial Recovery Act) impeded full recovery by artificially keeping prices and wages high and reducing efficiency . These arguments remain debated, but they highlight that even the recovery phase of the 1930s has competing interpretations—whether the slow return to normalcy was due to insufficient stimulus or misguided regulation.

Shifts in Historiography over Time

Over the many decades since the 1930s, historiography of the Great Depression has shifted as new evidence and methodologies emerged. Immediately after the Depression, the dominant narrative was essentially that of failure of laissez-faire capitalism – an interpretation that empowered the Keynesian policy revolution. By the 1950s and 1960s, as noted, Keynesian economicsKeynesian Economics Full Description:The dominant economic consensus of the post-war era which argued that the government had a duty to intervene in the economy to maintain full employment and manage demand. Neoliberalism defined itself primarily as a reaction against and a dismantling of this system. Keynesian Economics underpinned the “Golden Age” of capitalism and the welfare state. It operated on the belief that unregulated markets were prone to collapse and that the state must act as a counterbalance—spending money during recessions and taxing during booms—to ensure social stability and public welfare.

Critical Perspective:From the neoliberal viewpoint, Keynesianism was a slippery slope to totalitarianism. However, critics argue the dismantling of this consensus broke the social contract between capital and labor. By abandoning the commitment to full employment and social safety nets, the state abdicated its responsibility to its citizens, prioritizing the health of the currency over the health of the population.

Read more reigned, and the Depression was attributed to demand failure and was used to justify active macroeconomic policy. In the 1960s and 1970s, Friedman and Schwartz’s work sparked a monetarist revision: they didn’t reject that demand fell, but re-framed the cause of that demand collapse in terms of monetary contraction and Fed errors. This led to intense debates between Keynesians and monetarists about whether fiscal or monetary forces were more decisive. By the 1980s and 1990s, a sort of synthesis emerged in academia often called the “new neoclassical synthesis” – recognizing that both monetary policy and real demand shocks mattered, and that the gold standard was a crucial international transmission mechanism. Economic historians like Barry Eichengreen brought global and institutional perspectives to the fore. Eichengreen’s influential book Golden Fetters (1992) demonstrated how the gold standard system fundamentally constrained and shaped countries’ responses, implicating it as “the mechanism by which the Depression was transmitted abroad” . This international view corrected earlier U.S.-centric analyses and showed the value of coordinated policy (or the harm of its absence).

Another historiographical development was the renewed interest in microeconomic factors: the role of banking structure, labor markets, and productivity. For example, studies have examined why unemployment stayed so high and why recovery was slow. Research into labor markets has considered whether sticky wages (wages not falling despite high unemployment) exacerbated joblessness – some New Deal policies aimed to keep wages up, which, while helping those employed, may have hindered new hiring. Others have looked at the recovery puzzle: despite substantial GDP growth after 1933, unemployment in the U.S. remained around 15% in the late 1930s (until war spending finally absorbed the slack). Explanations here vary, from insufficient government spending to structural shifts and the lingering effects of uncertainty.

Through all these debates, one finds that historians’ questions have evolved: early on it was “What caused the initial crash?”; later “Why did the downturn become so deep and last so long?”; and also “Why did recovery take so long and vary between countries?”. As Crafts and Fearon (2010) note, key questions include why a normal recession turned into a decade-long depression, why it spread worldwide, and what roles financial crises and policy played . Each generation of scholarship has added nuance. The consensus today incorporates elements from multiple schools: aggregate demand matters a great deal (validating Keynes), monetary factors and central bank actions are critical (validating Friedman/Bernanke), international gold-standard constraints were paramount (thanks to Eichengreen and others), and structural issues like debt, inequality, and institutional frameworks all played a part. The Great Depression is thus understood as a multifaceted event – a result of interacting economic failures rather than a single-cause story. This pluralistic view is reflected in modern surveys of the topic , which acknowledge that any full explanation must integrate domestic and global factors, policy and market forces, and acknowledge the validity of different analytical lenses.

Conclusion

The Great Depression and the collapse of global trade in the 1930s stand as a stark reminder of the fragility of the modern economic system. Long-term imbalances and structural flaws – from war debt traps and gold-standard rigidity to income inequality and weak banking systems – set the stage for disaster. Short-term triggers, especially the 1929 stock crash and successive banking crises, then ignited the conflagration. Compounding the situation were policy failures: the reluctance of central banks to intervene, the adherence to an inflexible gold standard, and the rush to protectionism all made a bad situation immeasurably worse. The resulting collapse of world trade and industrial output led to mass unemployment and hardship that profoundly shaped the course of world history in that decade, contributing to political extremism and eventually World War II.

Scholars have sifted through this calamity from every angle, yielding rich historiographical debates. Keynesian economists view the Depression as the ultimate demand failure, solvable by public spending – a lesson that reshaped economic policy after World War II . Monetarists, by contrast, emphasize how central bank mismanagement turned a downturn into a catastrophe, a perspective that has influenced central banking practice up to the present . Marxist and other radical analysts see in the Depression evidence of capitalism’s inherent instability and the consequences of unfettered capital accumulation . Each interpretation brings valuable insights, and together they provide a more complete understanding. The Keynesian focus on demand highlights the importance of preventing collapse in spending; the monetarist focus on money and banking highlights the need to maintain financial stability; the Marxist focus on inequality and overproduction highlights long-run structural health; the international focus (à la Eichengreen) reminds us that global economic integration means crises transcend borders and require cooperative solutions .

For students and history enthusiasts, the story of the Great Depression is a sobering one, but also illuminating. It led to major changes in economic thought and policy: the rise of macroeconomics as a discipline, the acceptance of a government safety net and financial regulations, and the creation of institutions to foster international economic stability (like the IMF and World Bank after WWII, aimed at avoiding the kind of unchecked collapse of the 1930s). In short, the legacy of the Great Depression has shaped our world, and the debates it sparked – Keynes vs. Hayek, government vs. market, internationalism vs. nationalism – continue to echo in contemporary discussions. By examining the Depression’s causes and the collapse of global trade through multiple lenses, we not only better understand that era, but also gain wisdom about preventing such a catastrophe from happening again. The lesson, as many historians conclude, is that economic prosperity is perishable unless we heed the warning signs and cooperate across borders – a lesson just as relevant today as it was in the 1930s.

References:

Bernanke, B. (2002). On Milton Friedman’s Ninetieth Birthday, speech, Federal Reserve Board (cited in Federal Reserve History summary) . Crafts, N. & Fearon, P. (2010). Lessons from the 1930s Great Depression. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 26(3): 285–317 . Eichengreen, B. (1992). Golden Fetters: The Gold Standard and the Great Depression, 1919–1939. Oxford University Press (summary of thesis in Eichengreen & Temin 2000) . Eichengreen, B. & Temin, P. (2000). The Gold Standard and the Great Depression. Contemporary European History, 9(2): 183–207 . Eichengreen, B. & Sachs, J. (1985). Exchange Rates and Economic Recovery in the 1930s. Journal of Economic History, 45(4): 925–946 (finding: early gold-exit aided recovery) . Field, A. (2016). n/a (Historiography overview) – as referenced in CREI working paper (historiography focused on aggregate demand) . Friedman, M. & Schwartz, A. (1963). A Monetary History of the United States, 1867–1960. Princeton University Press (monetarist analysis) . Keynes, J.M. (1936). The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money. Macmillan (Keynesian theory of demand deficiency). Keynes, J.M. (1931). An Economic Analysis of Unemployment (essay, quoted by Crafts & Fearon) . Kindleberger, C. (1973). The World in Depression, 1929–1939. University of California Press (emphasizing lack of hegemonic stabilizer) . Madsen, J. (2001). Trade Barriers and the Collapse of World Trade during the Great Depression. Southern Economic Journal, 67(4): 848–868 (tariffs and trade collapse) . Romer, C. (1993). The Nation in Depression. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 7(2): 19–39 (overview of comparative depressions). Temin, P. (1976). Did Monetary Forces Cause the Great Depression? (book). New York: Norton. Temin, P. (1994). The Great Depression. NBER Historical Working Paper No. 62 (argues gold standard was key) . U.S. Federal Reserve History Website (2022). Essay on The Great Depression by G. Richardson (overview of Fed and causes) . Smoot-Hawley Tariff ActSmoot-Hawley Tariff Act Full Description:A piece of US legislation that raised import duties to historically high levels in an attempt to protect domestic farmers and manufacturers. It is widely cited by economists as a disastrous policy error that triggered a global trade war. The Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act represents the height of economic nationalism. In a misguided effort to shield American jobs from foreign competition during the downturn, the US government taxed imported goods. This provoked immediate retaliatory tariffs from other nations, effectively shutting down the global trading system.

Critical Perspective:This act illustrates the danger of “beggar-thy-neighbour” policies—strategies that seek to improve a nation’s economic standing at the expense of its trading partners. Instead of protecting jobs, it destroyed the export markets that industries relied on. It serves as a historical lesson on how a lack of international cooperation and a retreat into isolationism can transform a recession into a global catastrophe.

Read more (1930). U.S. Tariff legislation, as discussed in Crafts & Fearon (2010) . Sweezy, P. (1942). The Theory of Capitalist Development. Monthly Review Press (Marxian interpretation). Cole, H. & Ohanian, L. (2004). New Deal Policies and the Persistence of the Great Depression. Journal of Political Economy, 112(4): 779–816 (arguing some policies prolonged depression) .

Leave a Reply