Introduction: The Diplomacy of Partition

The Asia Minor Agreement, concluded in May 1916 and retroactively known as the Sykes-Picot Agreement, stands as the foundational document of the modern Middle Eastern state system. While often reduced in popular discourse to an arbitrary division of territory, the agreement was, in reality, a complex diplomatic instrument designed to resolve a specific strategic crisis within the Triple Entente. By late 1915, the alliance between Great Britain, France, and Russia was strained by conflicting territorial ambitions regarding the Ottoman Empire. The agreement was a provisional compromise intended to prevent these rivalries from undermining the war effort against the Central Powers.

The negotiation of the treaty fell to two mid-level officials: Sir Mark Sykes of Britain and François Georges-Picot of France. Their task was to reconcile the irreconcilable: Britain’s desire for security in the Persian Gulf and a buffer for the Suez Canal, France’s historical claim to the Levant, and Russia’s demand for control of the Turkish Straits. The resulting map, signed in secret, established a framework of “spheres of influence” that treated the Arab provinces of the Ottoman Empire as administrative units to be distributed based on European logistical and economic requirements.

This article examines the origins and mechanics of the 1916 agreement. It analyzes the biographies of the two primary negotiators, the strategic deadlock that necessitated their appointment, and the specific territorial provisions that would eventually evolve into the mandate borders of Syria, Iraq, Lebanon, and Palestine.

The Negotiators: Divergent Approaches to Empire

The texture of the agreement was heavily influenced by the distinct backgrounds and ideological inclinations of the two men appointed to draft it. Their relationship reflected the broader tensions between the British and French empires—allies in Europe, but rivals in the colonial world.

Sir Mark Sykes: The Unorthodox Expert

Sir Mark Sykes (1879–1919) was an anomaly in the British diplomatic establishment. A wealthy baronet and Conservative Member of Parliament, he was not a career official of the Foreign Office. His reputation as an expert on the “Near East” was built on extensive pre-war travels through the Ottoman domains and the publication of several travelogues.

Sykes was brought into the War Cabinet by Lord Kitchener, the Secretary of State for War, specifically to bypass the slow-moving bureaucracy of the Foreign Office. Sykes represented a “constructive imperialism.” He believed that the Ottoman Empire was doomed and that Britain must actively shape the post-Ottoman order to secure its route to India. Unlike the traditionalists in Delhi (the Government of India), who preferred the status quo, Sykes advocated for a new structure involving Arab clients, though he initially viewed Arab nationalism through a paternalistic lens. His approach to negotiation was fluid and often impressionistic, prioritizing broad strategic concepts over legalistic detail.

François Georges-Picot: The Colonial Professional

In contrast, François Georges-Picot (1870–1951) was a veteran of the French diplomatic corps. Having served as the Consul-General in Beirut until the outbreak of war, Picot was intimately familiar with the Levant. He was a staunch advocate of the Parti Colonial, a pressure group within French politics that viewed the acquisition of “Greater Syria” (La Syrie Intégrale) as essential for French prestige and economic interests.

Picot’s mandate from the Quai d’Orsay was rigid. France claimed a historical protectorate over the Catholics of the East (specifically the Maronites) dating back to the capitulations of the 16th century. Picot viewed British support for an Arab Kingdom as a cynical maneuver to exclude France from the region. His negotiation style was defensive and legalistic, driven by a deep suspicion of British motives. He operated under the instruction that France must secure direct control over the Syrian littoral and the interior cities of Damascus, Homs, Hama, and Aleppo.

The Strategic Deadlock: The Necessity of Definition

The catalyst for the negotiations was the deteriorating military and diplomatic situation in late 1915. The Gallipoli campaign was failing, and the British were seeking new local allies to open a southern front against the Ottomans. This led the British High Commissioner in Cairo, Sir Henry McMahon, to open correspondence with Sharif Hussein of Mecca, discussing the possibility of an Arab Revolt in exchange for British support for Arab independence.

However, the British Foreign Office realized that any promise made to Hussein would inevitably collide with French claims in Syria. If Britain promised Damascus to the Arabs while France claimed it for itself, the Entente could fracture. The British government effectively paused the negotiations with Hussein to reach a prior understanding with France.

In November 1915, Sykes and Picot met in London to harmonize these competing claims. The core friction was geographical: Britain needed a secure land bridge from the Mediterranean to the Persian Gulf (the Haifa-Baghdad axis) to transport troops and, potentially, oil. France demanded the entirety of Syria. The challenge was to satisfy French territorial demands without severing British communications or totally alienating the potential Arab allies.

The Architecture of Partition: Zones of Control and Influence

The breakthrough in the negotiations came through the adoption of a tiered system of control. Rather than simple annexation, Sykes proposed dividing the region into zones of “direct control” and zones of “influence.” This allowed the powers to claim they were upholding the principle of Arab sovereignty (in the interior) while retaining economic and political dominance.

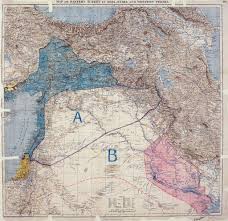

The agreement, finalized in draft form in early 1916, established five distinct administrative areas:

The Blue Zone (France):

This area covered the coastal strip of Syria and Lebanon (from Tyre to Alexandretta) and extended north into Cilicia (southern Turkey). Here, France was authorized to establish “such direct or indirect administration or control as they desire.” This satisfied Picot’s demand for the valuable ports of Beirut and Tripoli and protection for the Maronite communities.

The Red Zone (Britain):

This comprised the Ottoman vilayets of Basra and Baghdad in Mesopotamia. Here, Britain was granted similar rights of direct control. This secured the head of the Persian Gulf, the oil refinery at Abadan, and the Indian flank.

Zone A (French Influence):

This area encompassed the Syrian interior, including the major cities of Damascus, Aleppo, Homs, and Hama, and extended east to include the vilayet of Mosul. In this zone, France would recognize an independent Arab state or confederation of states but would retain “priority of right of enterprise and local loans” and would be the sole supplier of foreign advisors.

Zone B (British Influence):

This covered the desert territory between Palestine and Mesopotamia (modern-day Jordan and western Iraq), connecting the Red Zone to the Mediterranean. Similar to Zone A, Britain would recognize an Arab state but exercise exclusive economic and political influence.

The Brown Area (Palestine):

The most contentious issue was the status of Palestine. Picot demanded it for France; Britain refused to allow a major European power to flank the Suez Canal. The compromise was an international administration (the “Brown Area”) for Jerusalem and the Holy Land, the exact form of which would be determined after consultation with Russia and other allies. However, Britain secured control of the ports of Haifa and Acre to serve as a terminal for a future oil pipeline from Mesopotamia.

The Russian Dimension

While often omitted from general histories, the agreement was tripartite. Once Sykes and Picot agreed on the Anglo-French division, they traveled to Petrograd in March 1916 to secure Russian assent.

The Russian Foreign Minister, Sergey Sazonov, agreed to the partition on the condition that the Allies recognize Russia’s annexation of Constantinople, the Bosphorus Straits, and the Ottoman Armenian provinces (Erzurum, Trabzon, Van, and Bitlis). This created a ring of partition: Russia in the north, France in the middle, and Britain in the south. The formal exchange of letters ratifying the agreement took place between Foreign Secretary Edward Grey and Ambassador Paul Cambon on May 16, 1916.

The Geographic and Ethnographic Disconnect

The fundamental critique of the Sykes-Picot map is its prioritization of imperial logistics over local demographics and topography. The boundary line between the French and British spheres—running roughly from Kirkuk to the Mediterranean—dissected the natural economic unity of the region.

- Aleppo and the Coast: The agreement separated the commercial hub of Aleppo (Zone A) from its natural port at Alexandretta (Blue Zone) and its markets in Mosul (Zone A) and Baghdad (Red Zone).

- Tribal Confederation: The line cut directly through the grazing lands of major tribal confederations, such as the Shammar and the ‘Anizah, creating a border that was unenforceable on the ground.

- The Mosul Question: Originally, Mosul was assigned to the French Zone A. This was a geographical anomaly, as Mosul is naturally linked to Baghdad by the Tigris River. It was assigned to France solely to provide a buffer between the British in Baghdad and the Russians in Armenia.

The Unraveling of the Agreement (1917–1918)

The Sykes-Picot Agreement was a static document in a fluid war. By the time the conflict ended in 1918, the geopolitical realities had shifted so drastically that the original map was rendered partially obsolete.

The Bolshevik Leak: Following the Russian Revolution in 1917, the Bolshevik government discovered the secret treaty in the Tsarist archives. In a move to discredit the “imperialist war,” Leon Trotsky published the text in Izvestia and Pravda. The revelation caused a diplomatic crisis, particularly with the United States (which had entered the war under Woodrow Wilson’s banner of “no secret treaties”) and with the Arab leadership, who viewed it as a negation of the British promises made to Sharif Hussein.

The Revision of Mosul: Following the cessation of hostilities, British Prime Minister David Lloyd George successfully pressured French Premier Georges Clemenceau to cede Mosul from the French zone to the British zone. This was driven by two factors: the discovery of significant oil reserves in the region and the collapse of Russia, which removed the need for a French buffer in the north.

The Balfour Declaration: The “Brown Area” of international administration was also abandoned. Following the 1917 Balfour Declaration, which expressed British support for a “national home for the Jewish people,” Britain maneuvered to establish a singular British Mandate over Palestine, effectively removing France from the Holy Land entirely.

Conclusion: The Transition to Mandates

The Sykes-Picot Agreement was never implemented in its exact original form. The direct administration zones and the international zone in Palestine were modified by the San Remo Conference of 1920 and the League of NationsLeague of Nations

Full Description:The first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. Its spectacular failure to prevent the aggression of the Axis powers provided the negative blueprint for the United Nations, influencing the decision to prioritize enforcement power over pure idealism. The League of Nations was the precursor to the UN, established after the First World War. Founded on the principle of collective security, it relied on moral persuasion and unanimous voting. It ultimately collapsed because it lacked an armed force and, crucially, the United States never joined, rendering it toothless in the face of expansionist empires.

Critical Perspective:The shadow of the League looms over the UN. The founders of the UN viewed the League as “too democratic” and ineffective because it treated all nations as relatively equal. Consequently, the UN was designed specifically to correct this “error” by empowering the Great Powers (via the Security Council) to police the world, effectively sacrificing sovereign equality for the sake of stability.

Read more Mandate system. However, the agreement’s core legacy was the imposition of the nation-state model on the Middle East.

By dividing the region into British and French spheres, Sykes and Picot established the political trajectory of the Middle East in the 20th century. The merging of Basra, Baghdad, and Mosul created the state of Iraq; the separation of the Levant created the modern borders of Syria and Lebanon. While the specific lines shifted, the principle established in 1916 remained: the political geography of the Middle East would be determined by the strategic requirements of external powers rather than the internal dynamics of the region’s population.

Leave a Reply